ISSN: 2158-7051

====================

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

RUSSIAN STUDIES

====================

ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/2 )

|

ISSN: 2158-7051 ==================== INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES ==================== ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/2 ) |

VARIATION IN THE STRESS OF RUSSIAN FEMININE NOUNS OF MOBILE TYPES D (ЖЕНА́) AND D´(СПИНА́)

ROBERT LAGERBERG*

Summary

In this article two key mobile stress patterns of Russian are analysed, patterns d and d´. The former is characterised by ending stress in the singular and stem stress in the plural, while the latter has the same pattern except for the accusative singular which has stem stress, i.e. it has a mobile sub-paradigm in the singular. Pattern d has been established as not only the largest mobile stress type among first-declension feminine nouns, but also the only pattern which is in the ascendancy. This article attempts to analyse empirically what variation exists within nouns of this paradigm, since it is to be expected that variation would indicate earlier stress types ‒ as an ascendant type, pattern d itself would be expected to be stable as an endpoint for nouns from other stress types, particularly patterns d´, f and f´. Pattern d´ is also briefly analysed in order to establish whether it can be considered a sub-type of pattern d in the sense that nouns which have variation tend to be moving towards pattern d. The hypotheses for both patterns are borne out by the data: pattern d is largely stable and most variation which occurs within it indicates earlier stress types, while pattern d´ exhibits a weak tendency towards pattern d. Key Words: Russian language, accent, word stress, mobile stress, phonology. Introduction This article analyses the dynamics of two

mobile stress types in Russian feminine first-declension nouns which are generally referred to as patterns d and d´ (for example, in Zaliznjak 1977). By examining the development of such

patterns over a period of approximately forty years using normative and

descriptive sources of Russian, as well as data from other linguistic accounts

and surveys, a fuller picture is given of the directions of change in which the

accentual complexities of such nouns are moving. The two most common mobile patterns

of feminine first-declension nouns in Russian are patterns d and pattern f: for

example, Fedjanina (1982, 82-83) lists 120 nouns of type d, 35 of type f.[1]

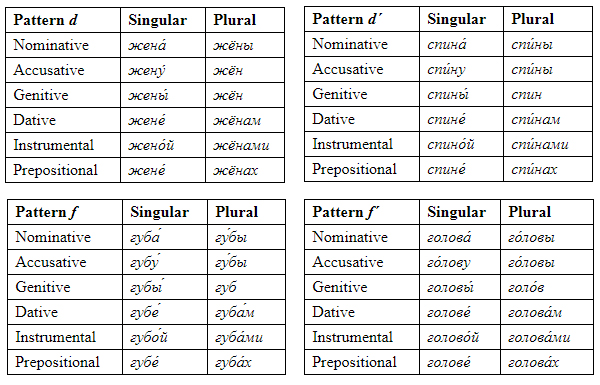

Pattern d is represented by ending stress in the singular sub-paradigm and stem stress in the plural sub-paradigm (e.g. жена́ ‘wife’), while pattern f has ending stress throughout the singular and plural sub-paradigms, except for the nominative/accusative plural, which has stem stress on the initial stem syllable (e.g. губа́ ‘lip’). In nouns of more than one syllable, the genitive plural with zero ending generally has stress on the final syllable (e.g. голо́в). In addition to these two main types of mobile stress, two related sub-types, each with retracted accusative singular stress, also occur, namely pattern d´ (which will form much of the discussion of this article) and pattern f´: thus, pattern d´ has the same pattern as d, but with stress retracted on to the initial stem syllable in the accusative singular (e.g. спина́ ‘back’), while pattern f´ is identical to pattern f, but with the same retraction of stress (e.g. голова́ ‘head´). The focus of this article is feminine nouns of the types d and d´, though mention of patterns f and f´ will frequently be made. For convenience, all these complex feminine mobile paradigms are laid out below:

Pattern f

Within

the study of inflectional Russian stress, feminine first-declension nouns of

(typically) two, (sometimes) three and (rarely) four or more syllables with

mobile stress represent the classical area as a result of their strong

connection with the more complex Proto-Slavonic stress and intonation patterns

(i.e. those with desinential and mobile stress), a complex history of

subsequent variation in terms of their development from Old Russian into the

modern era, as well as their current tendency to display high levels of

variation in the standard language. As early as 1952, Hingley (1952, 187) made

some important observations on both the history and future directions of

(complex) Russian stress, writing that the “flexional stress of nouns in -а/-я has undergone a certain evolution, that it is

in a state of flux at the present moment, and that it may be expected to move

in a certain predictable direction in the future.” He continues (ibid., 195): “It

therefore seems likely that words have tended to defect from the fixed final paradigm to a

mobile paradigm in proportion to the frequency with which they are used.” And

further (ibid, 196): “The condition of apparent chaos in the flexional stress

of disyllabic mobile nouns in -а/-я becomes intelligible when

it is realised that Russian is in a process of establishing a new paradigm

which has already achieved such ascendancy that it has assimilated more than

half of the material. In the new paradigm columnar stress on the case-endings

of the singular is opposed to columnar stress on the stem throughout the

plural.” Hingley is here making two key points concerning Russian mobile stress

in feminine first-declension nouns: a) he links the adherence of various words

to their respective stress patterns with their respective frequency (without,

however, verifying this in any empirical way), and, b) he recognises the

ascendancy of the d paradigm, that

is, a paradigm with fixed stem stress in the singular and fixed stem stress in

the plural, i.e. a columnar type of stress pattern with the singular and plural

clearly demarcated.

Exactly fifty years later, Nick Ukiah (Ukiah 2002) published an article on the current situation in Russian vis-à-vis the f pattern of Russian feminine nouns. This article, in a sense, continues where Hingley left off: it attempts to establish the current situation, at least in spoken, spontaneous Russian, with regard to the tendencies in the stress patterns of nouns which, at one stage, have been held to belong to the f pattern.[3] The specific aim of Ukiah’s survey is to ascertain the accentual tendencies of these nouns with variation, and, in particular, whether they are undergoing either of two important tendencies currently at work in the Russian stress system: a) a general tendency in Russian mobile stress towards a singular/plural opposition; in the case of the губа́-pattern nouns we are dealing here with ending stress in the singular and a shift to a contrasting fixed stem stress in the plural (i.e. a move to stress pattern d), or, b) a general tendency in Russian mobile stress towards a differentiation of stress in the plural forms only; in the case of pattern f, the direct cases (i.e. nominative, accusative) would have stem stress and the oblique (genitive, dative, instrumental and prepositional) cases would have ending stress, i.e. in this scenario the f-pattern is simply retained, itself representative of the general tendency. The genitive plural, as Ukiah makes clear (2002, 5-6), representing a reduction of syllables in the case of most of these words, often to one syllable (e.g. губ), would, of course, play a central role in such a development, since it forces the otherwise (at least, assumed, on the basis of the f-pattern oblique cases) desinential stress on to the stem, thereby blurring the boundary between the direct and oblique cases and creating the potential for analogous or alternative stem stress in the remaining oblique plural forms.[4]

A wider historical perspective on the

development of the Russian f stress pattern

is instructive, as it has a direct relationship with pattern d nouns, and this is an area that is

currently in a state of flux, moving from one system to another. In terms of

‘classical’ Slavonic accentology, as exemplified by, for example, Vaillant

(1950), pattern f ultimately goes

back to the (hypothetical) Common Slavonic pattern b (characterised by fixed stress on the ending), which itself came

about in the following way (Vaillant 1950, 246): ‘une

tranche d´intonation douce a attiré l’accent de la tranche brève ou d´intonation

douce qui la précédait.’ This process

is known as the ‘law of de Saussure’, but its validity has not been accepted by

all scholars: some revisionists (beginning with Stang (1957) and continuing

with, amongst others, Dybo (1981)), reject it partially, and at least one

(Darden 1984) rejects it entirely (albeit in an ‘experimental’ way).

Nevertheless, while disputing its origin, all scholars admit the existence of

an early class of desinentially stressed nouns. It is

important to distinguish this pattern b

class (e.g. черта́) from the already existing class of ‘true’ mobile (pattern f´) nouns (e.g. голова́, рука́, вода́). The latter mobile first-declension feminine nouns, unlike the newer b class, were characterised by a

recessive (i.e. shifting back to the initial syllable) stress in certain forms,

such as the accusative singular and nominative plural, which also shifted to a preposition when directly preceding the noun (a feature which still exists, though decreasingly so, it seems, in modern

Russian), e.g. за́ руку

‘by the hand´, на́ голову

‘on to the head’.[5] This

mobile stress pattern is regarded as the ‘classical’ mobile pattern of Russian,

now generally classified as pattern f´

(e.g. the stress paradigm of голова́). The pattern-f nouns (those exemplified by губа́), on the other

hand, emerged subsequent to and as an off-shoot of both this existing ‘pure’

mobile class, as well as the newer class of nouns with fixed ending stress, in other

words, they appear to be a later (circa

1600)

development, maintaining a fixed ending-stress for the majority of their forms

(i.e. pattern b), but shifting it on

to the stem in the nominative/accusative plural by analogy with pattern f´.

If, then, pattern f´

represents the oldest mobile type in Russian feminine nouns in -а/-я, the f (губа́) stress type is its direct heir, but resulted

more as a blend of a primarily pattern-b stress

with the characteristic f´ nominative

plural stress shift to the stem. The subsequent history of all these nouns

(roughly from the medieval period up to the end of the nineteenth century) is

one of volatile and erratic shifts of stress (see, for example, Kolesov (1972, 42), on the

retracted ‘mobile’ accusative singular stress for блоха́). However, the following clear tendencies through this maize can be

traced: the oldest type, pattern f´,

has been maintained in Russian, though many words which had previously belonged

to it, are no longer of this type (Fedjanina (1982, 100-101) lists only 13 such

nouns with this type of stress (CC in

her terminology)). Pattern b remains

in Russian, and is, indeed, statistically the second most frequent type for

first-declension feminine nouns, but has become very much a stress paradigm for

low or lower frequency nouns (see more on this below). Pattern f is less old and has been maintained in

such nouns as губа́

and блоха́. Still later patterns

emerging were pattern d´ and then

pattern d. The former resulted from a

reassignment of pattern f´ into a

stress pattern exemplified by земля́, which has the same stress has f´ nouns in the singular, but in the

plural has stem stress (a relic of the former pattern, however, being evident

in the genitive plural земе́ль, not *зе́мель). The more important

development in Russian, however, is represented by the later

emerging d paradigm, the most recent

of all the Russian mobile types (circa

1800), which is characterised by ending stress in the singular and stem stress

in the plural, i.e. this is a paradigm with columnar stress differentiated in

the singular and plural, and it is precisely this paradigm which is highlighted

by both Hingley (1952) and Ukiah (2002) as the apparent ‘goal’ of lower

frequency pattern-f nouns. Xazagerov

(1973, 102-106) also proposes that a columnar distinction in stress between

singular and plural is one of the key motivating facts in the dynamics of word

stress in modern Russian.

In

terms of modern Russian, both Hingley and Ukiah identify a link between a word’s

relative frequency and its stress pattern, but neither provides any

substantiated evidence for it. For each, however, the link is somewhat

different. Hingley (1952, 195) claims that there is a move away from fixed

ending stress (type b) in connection

with a word’s frequency, i.e. the more frequent the noun, the more likely it is

to have moved from pattern b to

pattern d (that is to say, to have

shifted its stress on to the initial stem syllable in all plural forms). As he

states (ibid.), ‘It therefore seems likely that words have tended to

defect from the fixed final paradigm to a mobile paradigm in proportion to the

frequency with which they are used.’ Indeed, feminine words with fixed ending stress (pattern b) are confirmed as a low frequency

group by Cubberley (1987, 34-35). Cubberley demonstrates that only 5 of the 357

most common (according to the data in Zasorina (1977)) feminine nouns in

Russian have pattern b, even though

they represent overall in Russian the second most common group (after the

pattern a fixed stress pattern)

according to Fedjanina (1982, 82), although she also states that they are mostly

rare, borrowed or Church Slavonic nouns (ibid., 93).[6]

Ukiah’s (2002) conclusion is somewhat different to that of Hingley: according to Ukiah (ibid., 23) nine f-pattern nouns appear to have retained pattern f for a majority of speakers. It is precisely this group of nouns which Ukiah assumes to have a relatively high frequency, since it is by virtue of their relatively high familiarity to speakers that they are able to maintain what is largely an anomalous, or at least complex, stress pattern (i.e. pattern f) and resist the ‘normalising’ tendency towards pattern d. As Ukiah writes (ibid., 21), ‘… many of the nouns remaining in pattern f appear to be rather common (i.e. high frequency) items of vocabulary, whereas many of those which have moved to pattern d appear to be rather rare.’ Further, according to Ukiah (ibid., 24), thirteen original pattern-f nouns appear, at least for the majority of speakers, to have moved to pattern d, so for these Ukiah would expect a relatively low frequency, i.e. they ‘appear to be rather rare’ (ibid., 21).

Lagerberg (2010) thereafter

demonstrated on the basis of Ukiah’s data that there is, indeed, some veracity to the claim that the stress of

feminine nouns in -а/-я and their relative frequency are linked.

However, the correspondence is not exactly as would be expected from Ukiah’s

suppositions and there remain inconsistencies in the data (e.g. outliers like де́ньги ‘money’ with high frequency but pattern d stress in standard Russian go against the hypothesis and require

alternative explanation), and, therefore, there exists a certain amount of

incertitude despite a generally positive result. It would not be unreasonable,

however, to add that such incertitude is one of the defining characteristics of

the study of Russian stress and its underlying system. What appears clear,

however, is that for feminine first-declension nouns, pattern d is establishing itself as the main

mobile paradigm. While pattern a is

undoubtedly the largest and most common pattern of stress for these nouns,

accounting for about 98% of all -а/-я nouns according to

Fedianina (1982, 81) and 76.7% of the 357 most common feminine nouns in Russian

according to Cubberley (1987, 35), pattern d

is now the most common mobile pattern, accounting for 7.3% of the 357 most

common feminine nouns according to Cubberley (ibid.), and 0.8% of all feminine nouns according to Fedjanina (see

Cubberley 1987, 38 for these figures) ‒ second only to pattern b nouns, though, as Cubberley (ibid., 35) shows, pattern b feminine nouns have an extremely low

prevalence among the most frequently used lexemes of Russian (only 1.4% of the

most frequent feminine nouns). In a sense, then, pattern-d nouns can be presented (both in theoretical, as well as

pedagogical terms) as the default and ascendant mobile pattern for

first-declension feminine nouns.

Aims

and approach

As shown above, the

main mobile types of stress for feminine first-declension nouns are pattern d (desinential stress

in the singular, stem stress in the plural (e.g. жена́)), pattern d' (as for pattern d but with

stress retracted on to the initial stem syllable in the accusative singular (e.g.

спина́ ‘back’)), paradigm f (desinential

stress throughout, except for the nominative plural which has stem stress on

the initial stem syllable (e.g. губа́ ‘lip’)), and pattern f'

(as pattern f, but with stress

retracted on to the initial stem syllable in the accusative singular (e.g. рука́

‘hand’, голова́

‘head’)). If, as is thought or

shown to be the case by various scholars (see Xazagerov 1973, 102-106 and Ukiah

2002, 25 respectively), that the general direction of mobile inflectional stress is towards a

columnar opposition between singular and plural, e.g. desinential stress in the

singular vs. stem stress in the plural, then it is pattern d which emerges as the key paradigm in the future development of

Russian mobile stress of feminine nouns. Since patterns d´, f and f´ all contain at least one stem

stressed form in the plural, it is logical that they will come under increasing

analogical pressure from the d type

(particularly in lower frequency lexemes), initially producing variants in the

relevant ‘anomalous’ (from the point of view of pattern d) grammatical cases and ultimately a columnar desinential/stem

stress type characterised by pattern d.

The ‘anomaly’ of the retracted accusative singular (types d´ and f´) would also be

overridden by analogy to a singular desinential type of stress, again,

presumably, first in lower frequency nouns and subsequently spreading beyond

that to encompass all such nouns.

The aim of this article is to test the above hypotheses, first and foremost in nouns with pattern d, and also in its subgroup, pattern d´. Indeed, from the point of view of the dynamics of word stress, the question of whether the latter pattern behaves as a subgroup of the former pattern is one that needs to be examined. The method taken is to compare the data found in two normative accounts from the same period approximately (Zaliznjak 1977 and Fedjanina 1982) with that found in a recent Russian orthoepic dictionary containing some 12,000 entries on variation and difficult cases of pronunciation and word stress (Gorbačevič 2010) by a prominent expert in the area of accentuation, K.S. Gorbačevič (see, for example, discussions of word stress in Russian by Gorbačevič (1978a, 1978b)). In this way, changes in stress over the last forty years approximately can be examined. The hypotheses are: a) because pattern d is in the ascendancy, a majority of nouns of this type in normative sources (Zaliznjak 1977 and Fedjanina 1982) are stable from the accentual point of view and, therefore, do not show variation and do not appear in Gorbačevič 2010; b) that instances of stress variation in Gorbačevič 2010, generally indicate movement towards pattern d from low- or mid-frequency nouns of patterns f, f´, d´ and possibly even b (with a realignment of the plural forms with ending stress to fixed stem stress).

Apart from its extensive size (around

12,000 units) and the expertise of its author, Gorbačevič 2010 is also noteworthy for the fact that it

provides stylistic comments on most stress variants, unlike, for example, Rezničenko

2003, another fairly recent orthoepic dictionary of Russian, which simply lists

variants without comment. These stylistic comments or deprecations in Gorbačevič 2010 allow us to make certain inferences about

the direction of accentual change. They are arranged in descending order of

correctness from ‘acceptable’ (‘допустимо’) to ‘not recommended’ (‘не рекомендуется’) to ‘sub-standard’ (‘просторечие’) to ‘incorrect’ (‘неправильно’) (ibid., 9-11). Although these are

not scientifically delineated categories, being ultimately the ‘subjective

pick’ of the author, nevertheless, they do provide an indication of increasing

to decreasing tendency with regard to stress shifts in the direction of the deprecated variant. Thus, if we take

‘acceptable’ to represent the strongest degree of variation, ‘not recommended’

can be termed ‘strong’, substandard as ‘weak’ and ‘incorrect’ as ‘very weak’. In

addition, two temporal deprecations, ‘obsolescent’ (‘устаревающее’) and ‘obsolete’ (‘устарелое’), represent stress shifts away from the stress of the deprecated

variant, ‘obsolete’ representing a more advanced, indeed, complete stage

than the ongoing ‘obsolescent’. It is these two latter deprecations which would

be expected to feature in pattern-d

nouns with variation (i.e. movement from patterns f, f´, d´ and b towards d).

Frequency is also used in the analysis. On the

whole, frequency sources are scarce in Russian. Although hitherto Zasorina

(1977) was generally regarded as the fundamental reference book on frequency in

Russian (see, for example, Cubberley 1987, which makes extensive use of this

work), Sharoff’s more recent online Russian frequency list (further referred to

by the abbreviation RFL) now comprises

the largest corpus to date (50,000 words), as well as being more contemporary

in terms of the usage which it is based on.[7]

Frequency and assimilation are, of course, closely connected, as discussed by Zaliznjak

(1977a, 75). Assimilated

words are defined as those with which speakers of Russian are familiar in the

course of their everyday or professional lives; unassimilated words are those

words with which such speakers are generally not familiar, since they are

connected, for example, with other countries, professions, historical eras or

social/professional groups, or they are words with which a given speaker has

only recently become acquainted. Zaliznjak (ibid.), although conceding the

limitations of being able to know for certain the status of assimilation of

every lexeme, suggests a three-way division of the total Russian vocabulary

into commonly used (e.g., хлеб‘bread), generally known (e.g., болт

‘bolt’) and not

generally known (e.g., гарт‘typemetal’). Using informal methods

(including asking native speakers their knowledge of random vocabulary items), RFL (50,000 words in total) is henceforth in this article broken

down into high-frequency lexemes (the

most frequent 10,000 words in RFL), mid-frequency lexemes (the following

30,000 lemmas in terms of frequency in RFL)

and low-frequency lexemes, represented by the remaining 10,000

lemmas in RFL plus those which do not

occur in it at all.

Data and analysis

In this

section, data from Gorbačevič

2010 is compared with

normative data from Fedjanina 1982 and Zaliznjak 1977, firstly for pattern-d nouns and then for pattern-d´ nouns. Kiparsky 1962 also provides

information on the original stress types of some of these nouns, and Ukiah’s (2003) comments on pattern-d´ nouns are also included where relevant. Although Fedjanina 1982 and Kiparsky 1962 use different systems of

stress notation (e.g. pattern f is

pattern BC in Fedjanina, type B in Kiparsky), only Zaliznjak’s system

will be used in this article in order to avoid confusion and needless

complexity, i.e. Fedjanina’s and Kiparsky’s systems are adapted to Zaliznjak’s.

As Zaliznjak 1977 and Gorbačevič

2010 are

lexicographical (alphabetical) sources, page numbers in them are not given. The frequency types given, namely high, mid and low, have been

discussed in Section 2 above.

Pattern d

In this section feminine nouns with

normative stress pattern d (the list

is taken from Fedjanina 1982, 95-97, BA

stress pattern) are examined and compared with Gorbačevič 2010. As stated

above, the hypotheses are that: a) a majority of nouns with original

or normative pattern d do not show

variation within this mobile paradigm and, thus, do not appear in Gorbačevič 2010; b) that instances of stress variation in Gorbačevič 2010 generally indicate movement towards pattern d from original patterns f, f´,

d´ and also b, with (low) frequency as a possible factor.

To begin with, however, in line with

the first hypothesis, more than half of the nouns of type d listed by Fedjanina (1982, 95-97), 63 out of 120, do not display

any variation and do not, therefore, appear in Gorbačevič 2010. This is clear evidence of a high degree of stability

in pattern-d nouns and supports the

first hypothesis. These nouns are as follows (frequency levels are put in

brackets, high - H, mid - M and low -L): aрба́

‘bullock cart’ (М), басма́ ‘seal

with imprint of khan’ (L),[8]

беда́ ‘misfortune’ (H), блесна́ ‘spoon-bait’ (М), блоха́ ‘flea’

(М), быстрина́ ‘rapid’

(L),[9]

вдова́ ‘widow’ (H), ветла́ ‘willow’

(L), ветчина́ ‘ham’

(М), вина́ ‘fault’

(H), война́ ‘war’

(H), высота́ ‘height’

(H), вышина́

‘height’ (М), глубина́ ‘depth’

(H), гроза́

‘storm’ (H), десна́ ‘gum’

(М), длина́ ‘length’

(H), длиннота́ ‘length,

prolixity’ (L), долгота́ ‘length,

longitude’ (М), доха́ ‘fur coat’ (М), дрофа́ ‘bustard’

(L), дуга́ ‘arc’

(H), дыра́ ‘hole’

(H), жена́ ‘wife’

(H), звезда́

‘star’ (H), змея́

‘snake’ (H), игра́ ‘game,

play’ (H), икра́ ‘calf

(of leg)’ (L), кирка́ ‘pick-axe’

(М), кислота́ ‘acidity’

(H), колбаса́

‘sausage’ (H), красота́ ‘beauty’

(H), крупа́ ‘cereals’

(М), леса́

‘scaffolding’ (L), лиса́ ‘fox’

(М), лукá ‘pommel’

(М), луна́

‘moon’ (H), мерзлота́ ‘frozen

condition of ground’ (М), мета́ ‘goal’

(М), нужда́ ‘need’ (H), ольха́

‘alder’ (М), пастила́

‘pastila (sweet)’ (L), пешня́ ‘ice-pick’

(L), пила́ ‘saw’

(М), плюсна́ ‘metatarsus’

(L), пола́ ‘skirt’

(H), пустота́ ‘emptiness’

(H), пчела́ ‘bee’

(М), седина́ ‘grey

hair’ (М), скорлупа́

‘shell’ (М), слюда́ ‘mica’

(М), смола́ ‘resin’

(L), среда́ ‘environment’

(H), старшина́ ‘sergeant

major’ (H), стопá ‘ream;

metric foot; pile’ (H), страда́ ‘toil’

(М), стрекоза́

‘dragonfly’ (М), стреха́ ‘eaves’

(L), тавлея́ ‘chess

board’ (L), тошнота́ ‘nausea’

(М), уда́ ‘hook’

(М), частота́ ‘frequency’

(H), широта́ ‘width’

(М). In total there are 13 nouns with

low frequency (20.6 %), 25 with mid frequency (39.7 %) and 25 with high

frequency (39.7 %). This contradicts the hypothesis of Hingley 1952 discussed

above, since the vast majority of nouns with stable pattern d and mid to high frequency is,

therefore, approximately 80%.

In addition to this feature of pattern-d nouns, previous research has identified an

ongoing shift of stress in Russian feminine first-declension nouns from pattern

f to pattern d, particularly in nouns with a lower frequency. In the following

ten nouns, clear evidence was found (Ukiah 2002, 24) of a shift towards pattern

d: волна́ ‘wave’ (also ‘wool’ as dialect singulare tantum), копна́ ‘shock, stook (of corn)’, межа́ ‘boundary-strip’, серьга́ ‘earring’, скоба́ ‘clamp’, сковорода́ ‘frying-pan’, слобода́ ‘settlement with non-serf population’, строфа́ ‘stanza, strophe’, тропа́ ‘path’ and щепа́ ‘splinter’. Of these nouns, seven were found (Lagerberg

2018, 92) to have mid frequency (out of a total of fourteen such nouns with mid

frequency) and three high frequency (out of a total of twelve such nouns with

high frequency), confirming that there is some correlation between frequency

and the probability of a stress shift to pattern d: only a quarter of the nouns with high frequency show this

tendency, as opposed to half of those with mid frequency. This feature is shown

particularly clearly, in fact, by the reverse phenomenon, whereby

high-frequency nouns with pattern f can

be shown to be retaining this stress type: thus, the data in Gorbačevič 2010 suggests that nine nouns (i.e. 75% of pattern-f

nouns with high frequency), viz голова́

‘head, person in charge’, губа́

‘lip’, железа́

‘gland’, ноздря́

‘nostril’, простыня́

‘sheet’, пята́

‘heel’, свеча́

‘candle’, слеза́

‘tear’and строка́

‘line’, all of which have high frequency with the exception of пята́ which

has mid frequency, are currently not showing any tendency to move from pattern f to pattern d. A connection between high frequency and accentual stability with

regard to pattern f can, therefore,

be clearly established, whereby high frequency acts as a barrier against nouns

moving to pattern d, as well as the

reverse phenomenon, whereby low-mid frequency results in a freer flow of nouns

from pattern f to pattern d.

There now follows an analysis of pattern-d nouns listed both in Fedjanina 1982 and in Gorbačevič 2010 (with variant stress forms):

верста́

‘verst’

Zaliznjak

1977 and Fedjanina (1982, 96) have pattern d,

though the latter, incorrectly, one presumes, includes it also in d´ (ibid., 100) as a noun which moves

stress on to the preposition (e.g. на́ версту). High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 classifies it as pattern d, but also mentions that the accusative

singular вёрсту is archaic (thus previous pattern d´ or f´ ?)

and that the prepositional plural (and, presumably, the dative and

instrumental) allows both stem and ending stress without differentiation (вёрстах,

верста́х). Kiparsky (1962, 211-212, 229,

231) suggests original pattern f´

moving to pattern d, but an

intermediate stage of d´ cannot be

confirmed. The oblique plural cases with ending stress in Gorbačevič 2010, although not stated as such, support an

earlier f´ and/or d´. High frequency as a restrictive factor

appears to have been overridden in this case in an ongoing shift from f´ > d´ (?) > d.

весна́ ‘spring’

Zaliznjak

1977 and Fedjanina (1982, 97) have pattern d.

High frequency. Gorbačevič

2010 has pattern d, but also gives the accusative singular

form вёсну

which is deprecated

as

‘неправильно’,

thus showing a weak tendency towards d´.

Kiparsky (1962, 212) suggests an original pattern f´ developing into d´ and

then d. Pattern d is, therefore, relatively stable in this high-frequency noun. The

evidence of Gorbačevič

2010 may, in fact,

point to a residual tendency towards f´

and/or d´.

волна́ ‘wave’

Both Zaliznjak

1977 and Fedjanina (1982, 96) have patterns d

and f without any stylistic or other

distinction. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010

also gives d and f, however, pattern d is

treated as ‘допустимо’,

thus suggesting an ongoing shift from f to

d. Kiparsky (1962, 204) treats

pattern b (fixed ending stress) in

fact as the most likely original pattern which went into decline in the

sixteenth century; subsequently the noun moved from pattern f to d.

It appears, therefore, that pattern d is

essentially the default pattern for this noun, though the move from pattern f is probably being restricted by high

frequency.

глава́ ‘head;

cupola; chapter’

Both Zaliznjak

1977 and Fedjanina (1982, 96) have pattern d

without variation for all meanings of this noun. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d, but also an archaic

(‘устарелое’) pattern b, which is also suggested by Kiparsky

(962, 213) as the norm as late as the nineteenth century. This noun, therefore,

has moved from type b to d.

заря́ ‘dawn,

sunset; reveille (military)’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) has pattern d (nom. pl. зо́ри) for the meaning ‘рассвет’. Zaliznjak 1977 also has pattern d for this meaning, but pattern f as archaic; for the meaning

‘reveille’, a noun with fixed stem stress is given, i.e. зо́ря. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 also has pattern d with pattern f deprecated

as ‘устаревающее’, but also includes the accusative

singular form зо́рю

for the meaning

reveille (pattern d´). Although not

without some uncertainty, Kiparsky (1962, 215) suggests type f´ as original (though type b is also possible), later transitioning

to pattern f and then d by the twentieth century. Like Gorbačevič 2010, he also cites evidence of a separate

pattern d´ for the meaning

‘reveille’. Leaving aside the secondary meaning ‘reveille’, which, it seems,

now has a separate form зо́ря,

this noun appears to have followed a route from pattern f´ to f and then d.

зола́ ‘ashes’

Fedjanina

(1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 both have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has ending stress for singular forms (though

no plural forms, thus, one can tentatively assume pattern d), and pattern d´ (acc.

sg. зо́лу) as ‘устарелое’. As a result of a lack of

comparative sources and also plural forms of this noun (which is treated by

some dictionaries as singulare tantum),

Kiparsky (1962, 216) is unable to ascertain the original type, but tentatively

suggests a path from pattern f´ to

pattern d, possibly with an

intermediate d´.

игла́ ‘needle’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 both have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular и́глу)

is ‘устарелое’. The

alternative genitive plural form и́гол

(as opposed to standard игл)

is also described as ‘archaic’. А weak tendency towards pattern f (prepositional plural на игла́х

‘неправильно’)

is certainly unexpected and hard to explain unless as residual pattern f. Kiparsky (1962, 216) gives an

unambiguous path from original pattern f´

to a later (nineteenth century) f and

then d.

изба́ ‘peasant

hut’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have patterns d and d´ without any

stylistic distinction. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(acc. sing. и́збу) is

‘устаревающее’. Kiparsky (1962, 216) finds strong evidence

for original pattern f´ with the

shift to pattern d (with some

instances of pattern d´ also)

beginning in the early 19th century. This noun, therefore, is

another good example of the postulated stress shift f´ > d´ (?) > d which, in this case, has overridden

high frequency.

коза́ ‘she-goat’

Fedjanina

(1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 both have pattern d without variation, although the latter source also includes the

idiom драть (бить,

лупить)

как сидорову ко́зу ‘to beat black and blue’, thus suggesting an

alternative older mobile pattern. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

or f´ (accusative singular ко́зу) is

‘устарелое’, also citing

the phrase драть как сидорову ко́зу as evidence of the earlier pattern. Kiparsky

(1962, 217) finds evidence for an original pattern f´, later becoming pattern d in

twentieth-century sources. The form ко́зу,

therefore, appears to go back to pattern f´.

Once again high frequency has not been able to prevent the shift towards

pattern d which is now normative.

коса́ (‘plait’)

See 3.2

below.

коса́ (‘scythe’)

See 3.2

below.

лоза́ ‘rod,

withe, vine’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010

has pattern d as normative, while

pattern d´ (or f´) (accusative singular ло́зу) is ‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 218) finds

evidence for an original pattern f´,

later becoming pattern d in

twentieth-century sources.

метла́ ‘broom’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010

has pattern d as normative, but the

unexpected instrumental plural form метла́ми

(‘неправильно’) which is hard to account for

unless one considers it to be influenced by the original pattern f´ (Kiparsky 1962, 218). The route for

this noun is, therefore, f´ > d notwithstanding high frequency.

нора́ ‘burrow’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular но́ру) is ‘устаревающее’. Kiparsky (1962, 218) cannot reach

firm conclusions about the original type, but suggests pattern f´ or, perhaps, pattern b, both of which have competing claims. By

the twentieth century, however, pattern d

is the norm in lexicographical sources (ibid.). The route taken by this noun

seems, therefore, to be of the general type postulated, notwithstanding high

frequency: f´/b > d´ > d.

овца́

‘sheep’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular о́вцу) is

‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 218) finds evidence for an original pattern f´ which becomes pattern f as a result of the accusative singular

form овцу́

as early as the nineteenth century (e.g. in Krylov’s work circa 1820), later (twentieth century) becoming pattern d, but still with traces of a colloquial

pattern d´. Although the intermediate

stage is not entirely clear, this high-frequency noun follows the hypothesised

shift from f´ > d´/f > d.

орда́ ‘horde’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without any variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular о́рду) is

‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 219) finds evidence for an original pattern b with a subsequent shift of stress

which cannot be determined exactly ‒ either to pattern d, d´

or f: the evidence of Gorbačevič 2010 suggests pattern d´ as more likely. By the twentieth century, however, pattern d is the norm in lexicographical sources

(ibid.). Although the intermediate stage is not entirely clear, this noun

follows the hypothesised shift from b

> d´ (?)/f (?) > d.

оса́ ‘wasp’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without any variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular о́су) is

‘устарелое’. Although contradicted by Serbian and Bulgarian accent patterns for

this noun (which suggest ending stress, pattern b), it seems that the original pattern was f´ and was still used in the nineteenth century (Kiparsky 1962, 220). By the twentieth century, however, pattern d had become the norm in lexicographical

sources (ibid.). The evidence of Gorbačevič 2010

could point either to the original pattern f´

or an intermediate pattern d´.

Perhaps the latter is more likely given the absence of any archaic variants

with ending stress in the plural in Gorbačevič 2010

(e.g. *оса́м),

thus f´ > d´ (?) > d.

плита́ ‘plate,

slab’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without any variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(accusative singular пли́ту) is ‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 220-221) is unable

to discern any distinct stress patterns for this noun’s early history, even

admitting the possibility of pattern a

and/or b, out of which eventually the

currently normative pattern d

emerged. The evidence of Gorbačevič 2010

points at least to the possibility of an intermediate pattern d´, which, as been shown above, can develop

from an older pattern b or, more

frequently, f´. A possible route for

this noun, therefore, could be a (?)

> b (?) > d´ > d.

просвира́ ‘communion

bread’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97 and 99) has pattern d for просвира́ (plural

therefore просви́ры, просви́р, просви́рам) and pattern f for the alternate (in church use) form просфора́ (plural

про́сфоры, просфо́р, просфора́м). Zaliznjak 1977 has pattern f for both forms. Low frequency. Although he does not give

the dative, instrumental and prepositional plural forms, Gorbačevič

2010 seems to be suggesting pattern f for

this noun, despite its low frequency, with ending stress in the singular and

mobility in the plural forms: про́сфоры, просфо́р / про́свиры, просви́р. Originally borrowed from Greek προσφορά

‘offering’, Kiparsky believes pattern f´

to be original, later changing to pattern f

for the form просфора́ and f/d

for просвира́.

Ukiah (2002, 11) finds that most of his respondents chose a partial pattern-d paradigm, with ending stress in the

singular, and, in the plural про́свиры, просви́р, просви́рам etc., i.e. the nominative/accusative and

genitive plural conform to pattern f,

but the remaining forms are pattern d,

possibly influenced by the position of stress in the genitive plural and the

low frequency of this noun. Ukiah (ibid.) also notes a possible levelling of

stress on the stem-final syllable throughout both paradigms, thus просфо́ра (which Gorbačevič

2010 also deprecates as ‘not recommended’), which could be influenced also by

the use of a diminutive form просфо́рка/просви́рка. This low-frequency noun, therefore, does not

support the hypothesis as it does not seem to be shifting from f to d.

река́ ‘river’

See 3.2

below.

роса́ ‘dew’

Fedjanina

1982 fails to include this word, though it is listed in the index as a pattern-d noun (ibid., 295). Zaliznjak also

gives pattern d without variation. Mid

frequency. Gorbačevič

2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´ (acc. sing. ро́су) is ‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 221) gives

pattern f´ as the original type,

still used as late as the nineteenth century. Pattern d appears to have stabilised in the twentieth century with some

possible variation with pattern f.

The route of this noun can be posited as f´

> f > d. The form in Gorbačevič 2010

is, therefore, unclear, but could be a residue of pattern f´.

руда́ ‘ore’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without any variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´

(acc. sing. ру́ду) is

‘устарелое’. Kiparsky (1962, 221-222) gives the original pattern as b, later becoming d without any intermediate stages discernible. The evidence of Gorbačevič 2010, however, points at least to the possibility

of an intermediate pattern d´. A

possible route for this noun, therefore, could be b > d´ (?) > d.

свинья́ ‘pig’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d, although the genitive plural is given as свине́й, i.e. on a

different syllable to the other plural forms (viz сви́ньи, сви́ньям

etc.). Zaliznjak 1977 also notes the (pattern f) stress свинья́м

used in abuse of the type ‘ну его

к свинья́м’ (‘well he can go to hell’ (literally, ‘him to the pigs’)). High

frequency. Gorbačevič

2010 has pattern d as normative, while pattern d´ (accusative singular сви́нью) is ‘устарелое’, and he also notes the dative

plural form свинья́м

used in abuse. Kiparsky (1962, 222) posits, albeit rather hesitantly as a

result of a lack of instances of this noun in his early Russian sources,

pattern f´, later (certainly by the

mid twentieth century) becoming pattern d.

The evidence of Gorbačevič

2010 is ambiguous: it

points at least to the possibility of an intermediate pattern d´, but also directly back to the accusative

singular stress of the original pattern f´.

The route for this noun, therefore, appears to be f´ > d´ (?) > d.

семья́ ‘family’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d, although the genitive plural is given as семе́й, i.e. on a different

syllable to the other plural forms (viz се́мьи, се́мьям etc.). High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, but also has variation in the accusative singular (семью́

vs. се́мью (‘устарелое’)) and in the instrumental plural (се́мьями

vs. семья́ми (‘устарелое’)). Kiparsky (1962, 222) is unable

to come to a clear decision about the original stress of this noun as a result

of a lack of south Slav correspondences and few instances of this noun in his

early Russian sources. Pattern f´,

however, appears to have been possible as late as the early nineteenth century

and this is borne out by the archaic forms in Gorbačevič 2010. The stress of this noun, therefore, appears

to have developed simply from pattern f´

to d.

сестра́ ‘sister’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d, although the genitive plural is given as сестёр, i.e. on a different

syllable to the other plural forms (viz сёстры, сёстрам etc.). Zaliznjak 1977 and Gorbačevič 2010 also have the proverb ‘всем сестра́м по серьга́м’

(‘everybody gets what they deserve’), indicating previous pattern f. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative, but also the accusative singular form сёстру

(‘неправильно’)

and variation in the plural oblique cases between normative stem stress and (‘устарелое’) ending stress, сестра́м,

сестра́ми.

Kiparsky (1962, 222) gives pattern b

as original, later developing to f (nineteenth

century) and subsequently pattern d (by

the twentieth century). The form сёстру

in Gorbačevič 2010 is anomalous. The route of the stress

of this noun, therefore, appears to be pattern b > f > d.

сирота́ ‘orphan’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 also has normative pattern d, but variation in the syllable

stressed in the plural forms: normative are сиро́ты,

сиро́т,

сиро́там

etc., while the alternative pattern-d forms

си́роты,

си́рот,

си́ротам

etc. are ‘неправильно’.

Kiparsky (1962, 222-223) gives pattern b as

original, later becoming pattern d by

the twentieth century. Kiparsky (ibid.) also notes the plural variants given in

Gorbačevič 2010, stating that the forms сиро́ты,

сиро́т,

сиро́там

are preferred in lexicographical sources. The stress of this noun, therefore,

has developed from pattern b to

pattern d.

скала́ ‘rock’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 also has normative pattern d, but variation in the accusative

singular between normative скалу́

and (‘устарелое’) ска́лу,

and in the plural between normative stem stress and (‘устарелое’) ending stress (скалы́,

скал, скала́м

etc.) which he states was still used widely in the nineteenth century,

particularly poetry. These archaic forms taken together do not point to one

stress pattern, but rather indicate patterns f, f´, d´ and b. Kiparsky (1962, 223) suggests that pattern b may have been original, subsequently perhaps developing into

pattern f´ (though this is not clear

and not supported by the nominative plural скалы́ in Gorbačevič 2010, although the accusative singular form ска́лу which he cites could indeed go back to pattern

f´) and only much later (late

nineteenth century or early twentieth century) into pattern d. The stress of this noun, therefore,

appears to have developed from pattern b to

pattern d with the possibility of an

intermediate stage of pattern f´.

скула́ ‘cheek-bone’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) pattern f (dative plural скула́м).

Kiparsky (1962, 223) finds evidence for an original pattern b, shifting to pattern f (by the nineteenth century) and

pattern d (by the twentieth century).

The variation in Gorbačevič

2010, therefore,

supports the existence of the intermediate stage (pattern f) in this noun’s development from pattern b to f to d.

слуга́ ‘servant’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) pattern f (dative plural слуга́м).

In a similar way to скула́

(above), Kiparsky (1962, 223) finds evidence for an original pattern b, shifting to pattern f (by the nineteenth century) and

pattern d (by the twentieth century).

The variation in Gorbačevič

2010, therefore,

supports the existence of the intermediate stage (pattern f) in this noun’s development from pattern b to f to d.

сноха́ ‘daughter-in-law’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but variation in the accusative singular between сноху́

and (‘устарелое’) сно́ху (suggesting a shift from

a previous pattern d´). Kiparsky

(1962, 224) posits pattern b as the

original stress type, subsequently becoming pattern f and then pattern d, but

no mention is made of pattern d´. In

this instance, therefore, there is a discrepancy between Gorbačevič 2010 and Kiparsky 1962. The possible route taken

by this noun is b > f/d´ (?) > d.

сова́ ‘owl’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but (‘устарелое’) ending stress in the plural, thus

pattern b (совы́, сов, сова́м

etc.). In a similar way to скула́ and слуга́ (above),

Kiparsky (1962, 224) finds evidence for an original pattern b, shifting to pattern f (by the nineteenth century) and

pattern d (by the twentieth century).

The variation in Gorbačevič

2010, therefore,

supports the existence of the first stage (pattern f) in this noun’s development from pattern b to f to d.

сосна́ ‘pine-tree’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) pattern a (nominative singular со́сна) and (‘устарелое’) pattern f (dative plural сосна́м).

The noun’s history is somewhat complex: Kiparsky (1962, 224) believes that

pattern a was indeed the original

pattern, later developing into f´

(though this is unclear) then d´ and/or

f, and finally stabilising pattern d possibly as late as the twentieth

century. Gorbačevič

2010, therefore,

describes the earliest pattern (a), the

intermediate pattern (f) and the

current norm (d).

софа́ ‘sofa’

Fedjanina

(1982, 96) has pattern d, while Zaliznjak

1977 has both patterns d and f. Mid frequency. Like Zaliznjak, Gorbačevič 2010 has both patterns d and f without

distinction (dative plural софа́м / со́фам), and also pattern a (со́фа) which is described as ‘устарелое’. Although the picture is not

entirely clear, Kiparsky (1962, 224) gives pattern b as the original type for this French loanword, subsequently

changing to patterns f and d (pattern a also appears in one source,

though is not recommended), with the latter the preferred type in

lexicographical sources.

соха́ ‘wooden

plough’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) d´ (acc. sg. со́ху). Pattern f

(dative plural соха́м)

is also given, but with the deprecation ‘неправильно’. Kiparsky (1962, 225) finds

evidence for an original pattern f´

which was still used by poets in the nineteenth century, subsequently shifting

to f and then d.

There is,

therefore, some discrepancy between Gorbačevič 2010

and Kiparsky 1962. If one accepts, however, the trajectory f´ > f > d, as given by Kiparsky, then Gorbačevič’s assertion of the plural

forms with ending stress as incorrect can perhaps be read rather as a residue

of pattern f.

страна́ ‘country’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) pattern b (nominative plural страны́).

Kiparsky (1962, 225-226) finds some evidence for original pattern f´ for this Church Slavonic loanword,

just as for the etymologically related Russian word сторона́ ‘side’

which still retains this stress pattern. However, there is also strong evidence

for early pattern b and even pattern a, and some evidence for an intermediate

stage of pattern f. Pattern d appears to have stabilised by the

twentieth century. The path of the stress of this noun, thus, appears to be f´/ b/ a (?) > f (?) > d.

стрела́

‘arrow’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’) pattern f´ (accusative singular стре́лу,

plural oblique cases стрела́м,

стрела́ми,

стрела́х).

Kiparsky (1962, 226) finds clear evidence for pattern f´, shifting to pattern f,

then d´ and finally d from around the start of the

nineteenth century. The archaic forms in Gorbačevič 2010 capture the original pattern of stress for

this noun.

стрельба́

‘shooting’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘неправильно’)

pattern f (dative plural стрельба́м).

Kiparsky (1962, 226) finds some evidence for an earlier pattern b, however, pattern d has stabilised by the twentieth century. Again, it is hard to

reconcile a possible ongoing shift towards pattern f as found in Gorbačevič 2010

with Kiparsky 1962. It is possible this tendency is in fact a residue of the

plural forms of the earlier pattern b.

строка́

‘line’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have patterns d and f without making any

differentiation between the two. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also

(‘устаревающее’)

pattern d´: accusative singular стро́ку.

Both Zaliznjak 1977 and Gorbačevič 2010

cite the proverb ‘не всякое

лыко в

стро́ку’ (‘everybody makes mistakes’)

with the accusative singular’s retracted stress. Kiparsky (1962, 209) finds it

hard to establish the history of this noun’s stress, mainly as the result of a

lack of a corresponding South Slavic noun, but suggests pattern f´ as original, later becoming f (possibly in the eighteenth century).

He makes no mention of pattern d

which could indicate that this is a much later twentieth-century development (f´ > f /d´ (?) > d).

строфа́ ‘stanza,

strophe’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have patterns d and f without making

any differentiation between the two. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 also has free variation between patterns d and f. He also warns against the

(‘неправильно’)

accusative singular stress стро́фу.

For this Greek loanword Kiparsky (1962, 209) suggests pattern b as original, later developing into

pattern f and finally stabilising as

pattern d as late the twentieth

century. Once again, it is hard to account for the non-normative accusative

singular form in Gorbačevič

2010. The stress of

this noun appears to have developed from pattern b > f > d, though pattern f still remains acceptable and even normative.

струна́ ‘string’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’)

pattern b (plural forms струны́,

струна́м

etc.). Although an original pattern a (стру́на) cannot be ruled out on the basis of Serbian

and Bulgarian, Kiparsky (1962, 226-227) finds evidence for an early pattern f in Russian itself and this was

considered normative by Vostokov in the nineteenth century. Pattern d appears to have stabilised only in the

twentieth century. There is therefore a sharp discrepancy between Zaliznjak

1977 and Gorbačevič

2010 in this case which

is represented thus: pattern a (?)

> f/b > d.

струя́ ‘stream, spurt’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) has pattern d, while

Zaliznjak 1977 has pattern d as

normative, but pattern b as poetic,

as does Gorbačevič

2010 also. High

frequency. Kiparsky (1962, 231-232) finds that pattern b is original, later moving towards pattern d (twentieth century), but still not to the exclusion of the earlier

type. Since then, as Gorbačevič

2010 demonstrates,

pattern d has become normative.

судьба́ ‘fate’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) has pattern d, as does

Zaliznjak 1977, but with an alternate genitive plural, viz су́деб / суде́б, especially in the idiom

‘волею

суде́б’ (‘as the fates decree’). He also

gives an alternate instrumental plural

судьба́ми as in the idiom

‘какими

судьба́ми?’ (‘by what

chance?’). Both of these forms go back to an original pattern b. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has pattern d as normative (the accusative singular су́дьбу is deemed ‘неправильно’ and is again hard to classify),

but also gives pattern b as

‘устарелое’ (plural forms

судьбы́, суде́б,

судьба́м etc.). This is

certainly confirmed by Kiparsky (1962, 227) who finds evidence for an original

pattern b, later becoming pattern d by the twentieth century with the

possibility of pattern f as an

intermediate stage (b > f (?) > d).

судья́ ‘judge, referee’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) has pattern d, as does

Zaliznjak 1977, but with an alternate genitive plural, viz суде́й / су́дей. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has the same classification as Zaliznjak

1977 (суде́й

is normative, су́дей

is ‘допустимо’, hence assumed to be an

innovation). Kiparsky (1962, 227) finds good evidence for an original pattern b, later (nineteenth century) becoming

pattern f and stabilising as pattern d in the twentieth century. The

stem-stressed genitive plural is likely, therefore, to be a late innovation in

order to bring the plural forms into alignment (су́дьи,

су́дей, су́дьям

etc.).

толпа́ ‘crowd’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’)

pattern b (plural forms толпы́,

толпа́м etc.). Kiparsky (1962, 227) finds

evidence for an original pattern b,

shifting to pattern f and then

pattern d by the twentieth century.

The variation in Gorbačevič

2010, therefore,

supports the existence of the original pattern in this noun’s development from

pattern b to f to d.

трава́ ‘grass’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’)

pattern d´ (accusative singular тра́ву).

Kiparsky (1962, 227) is unable to find clear evidence for this noun either in

old Russian sources or in south Slavonic languages (he posits pattern f´ for Serbian, pattern b for Bulgarian and Slovenian). However,

by the nineteenth century there is evidence of pattern f which becomes pattern d

in the twentieth century. There is, therefore, a discrepancy in the

intermediate stage of development between Kiparsky 1962 and Gorbačevič 2010: pattern f´

> f or d´ (?) > d.

тропа́ ‘path’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d and (archaic) pattern f.

High frequency. Gorbačevič

2010 also has normative

pattern d, but

(‘устарелое’) pattern f´: accusative singular тро́пу, plural oblique cases тропа́м, тропа́ми, тропа́х. Kiparsky (1962, 209) finds clear evidence for

an original pattern f´, with

vacillation as late as the twentieth century between types d, f and even b. Although the intermediate stages of

development are, therefore, somewhat clear, this noun has moved from an

original pattern f´ to d, most likely through the route f´

> f > d.

труба́ ‘pipe,

trumpet’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also (‘устарелое’)

pattern b (plural forms трубы́,

труба́м etc.). Kiparsky (1962,

228) posits pattern b for this German

loanword, shifting to pattern f in

the nineteenth century and stabilising as pattern d in the twentieth century, in agreement with the data in Gorbačevič 2010.

тюрьма́ ‘prison’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 97) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also the

(‘неправильно’)

accusative singular form тю́рьму

and (‘устарелое’) pattern

b (plural forms тюрьмы́, тюре́м, тюрьма́м etc.). Kiparsky (1962, 228) suggests pattern b as original for this Turkish loanword,

later developing into pattern f in

the nineteenth century and finally stabilising as pattern d in the twentieth century, in agreement with the plural forms in Gorbačevič 2010. Once again, it is hard to account for the

accusative singular form in this same source. The stress of this noun appears

to have developed from pattern b >

f >

d.

тягота́ ‘burden,

weight’

Fedjanina

(1982, 97) has pattern d with an

exceptional nominative plural stress, тя́готы

(*тяго́ты would be the expected stress).

Zaliznjak 1977 also has pattern d,

but this meaning is deemed obsolescent in favour of the noun тя́жесть:

тя́гота

(pattern a) is given as the stress position for the meaning ‘затруднение, забота’ (usually found in the plural). Mid

frequency. Gorbačevič

2010, like Zalzinjak

1977, has normative pattern a (nominative

singular тя́гота),

but also (‘устарелое’)

pattern b (тягота́,

plural forms тяготы́, тяго́т, тягота́м etc.). Kiparsky (1962, 228) finds evidence for

an original pattern b. Pattern b, therefore, can be taken as the

original stress type, later shifting to pattern d. However, in conjunction with a semantic change and the fact that

the noun is often used in the plural, the new plural stress (pattern d тя́готы)

has given rise to a completely new stress pattern a (тя́гота) with a different meaning

(‘difficulty, trouble’).

узда́ ‘bridle’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. Mid frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also ‘устарелое’ pattern d´ (accusative singular у́зду).

The plural forms (узды́,

узда́м

etc.), i.e. pattern b, are given as

‘допустимо’. Kiparsky

(1962, 228) suggests pattern b as

original, later developing into pattern f

in the nineteenth century and finally stabilising as pattern d in the twentieth century. Once again, there

is a discrepancy between Gorbačevič 2010

and Zaliznjak 1977. It is hard to account for the accusative singular form in Gorbačevič 2010, though, certainly, the plural forms seem to

go back to the original pattern b

rather than representing a tendency towards ending stress, even though they are

termed ‘acceptable’. The stress of this noun appears to have developed from

pattern b > f > d.

шкала́ ‘scale’

Both

Fedjanina (1982, 96) and Zaliznjak 1977 have pattern d without variation. High frequency. Gorbačevič 2010 has normative pattern d, but also

(‘неправильно’)

pattern b. As this noun does not

appear in Kiparsky 1962, it is hard to decide whether pattern b is original or a potentially new pattern,

though, as seen above, it is extremely unlikely for nouns to move from d to b,

thus the route b > d seems more probable. However, this, of

course, calls into question the nature of the deprecation ‘incorrect’.

Pattern d´

In this section twelve feminine nouns with

normative stress pattern d´ (the list

is taken from Fedjanina 1982, 99-100, CA

stress pattern (i.e. pattern d´)) are

examined and compared with Zaliznjak 1977 and Gorbačevič 2010. These nouns are вода́ ‘water’, дрога́ ‘centre

pole (of cart)’, душа́ ‘soul’, земля́ ‘land’, зима́ ‘winter’, изба́ ‘peasant hut’, коса́ ‘scythe’, коса́ ‘plait of hair’, река́ ‘river’, спина́ ‘back’, стена́ ‘wall’, цена́ ‘price’. As a small

group, it is to be expected that nouns belonging to it would have a relatively

high frequency, and, indeed, this is the case: дрога is the only noun of this type which

has low frequency, while all the others have high frequency.

The

main question to be answered is whether pattern d´ is indeed a subtype of or transitional path to pattern d, insofar as nouns of the former

pattern are gradually moving towards the latter (as shown above in 3.1, e.g. лоза́, оса́), particular those of low-mid frequency. As stated above in Section

1, it is assumed that pattern d´

originated from pattern f´and also f. Kiparsky (1962, passim) indeed posits

original pattern f´ for the majority

of all nouns which currently belong to pattern d´, namely вода́,

дрога́, душа́, земля́, зима́, изба́, коса́ (both

meanings), спина́,

стена́

and цена́.

For река́

alone (Kiparsky 1962, 207) an original type b

is posited, though not without considerable doubt.

With the historical path from

pattern f´ to d´ clearly

evident, it remains to be shown whether pattern d is the next link in this chain through the removal of mobile

stress in the singular, i.e. a move of stress in the accusative singular from

stem to ending. The following nine nouns (thus, 75% of all twelve pattern-d´ nouns) show variation in the

accusative singular in Gorbačevič

2010 (unless

otherwise stated, Zaliznjak 1977 has pattern d´):

земля́: зе́млю/землю́ (‘неправильно’)

зима́: зи́му/зиму́ (‘устарелое’)

изба́: избу́/и́збу (‘устаревающее’) (Zaliznjak 1977 has d/d´)

коса́ (‘plait’):

ко́су/косу́ (‘допустимо’) (Zaliznjak 1977 has d´/d)

коса́ (‘scythe’)

косу́/ко́су (‘реже’(‘more rarely’)) (Zaliznjak 1977 has d/d´)

река́: реку́/ре́ку (Zaliznjak 1977 has d´/d;

f´ (‘устар.’); Gorbačevič 2010 also has f´

as ‘устаревающее’ (река́м, река́ми, река́х))

спина́: спи́ну/спину́ (‘неправильно’)

стена́: сте́ну/стену́ (‘неправильно’) (Zaliznjak 1977 has d´; f´

(‘устар.’); Gorbačevič 2010 also has f´

as ‘устаревающее’ (стена́м, стена́ми, стена́х))

цена́: це́ну/цену́ (‘неправильно’)

With the exception of зима́

which has archaic ending stress in the accusative singular (which goes back to

an earlier (early nineteenth century, especially in poetry) pattern b according to Kiparsky (1962, 202)),

all the above nouns show a tendency either away from an older, now archaic

pattern d´ towards a currently normative

pattern d (изба́, коса́ ‘scythe’),

or towards a still non-normative pattern d

(indicated by

‘неправильно’

or ‘допустимо’) away from normative pattern d´ (земля́, коса́

‘plait’, спина́,

стена́,

цена́). In

the case of one noun, река́,

stylistic information is not present in Gorbačevič 2010, but a shift of d´ to d can be reasonably

assumed. These results essentially coincide with Ukiah’s (2003, 14) who sees

levelling of the accusative singular to ending stress in line with the rest of

the singular forms as characteristic, but also concedes that “a number of items

are nevertheless offering strong resistance to this movement.”

Conclusion

The two

hypotheses given above for nouns of pattern d

are largely borne out by the data. Firstly, nouns of this type can be seen to

be largely stable from the accentual point of view and do not display any

variation. In total, 63 of the 113 (i.e. over half, 55.8%) nouns of pattern d analysed in this article do not appear

in Gorbačevič 2010 as they do not have any

variation. As a stress pattern in the ascendancy, this is to be expected, but,

nevertheless, the lack of variation is striking given the relatively recent

shifts of most nouns to this pattern (often occurring in the nineteenth or

twentieth centuries). Frequency, however, as postulated by Hingley 1952 does

not appear to have played much of a role in this process: approximately 40% of

these 63 stable nouns are high frequency and another 40% mid frequency, leaving

only about 20% of them as low frequency nouns. This contradicts the notion put

forward by Hingley that pattern d attracts

primarily low-frequency nouns and, therefore, underlines its ascendancy all the

more.

Secondly, in the vast majority of

cases, nouns with variation in Gorbačevič 2010

are, indeed, ongoing shifts of stress from previous patterns (mostly f´ and b). However, frequency does not play the expected role: out of 47

nouns analysed in Section 3.1, 35 (74.5%) have high frequency, 11 (23.4%) mid

frequency and only 1 (2.1%) low frequency. Clearly nouns which are moving

towards pattern d, but have ongoing

variation, do so as a result of their higher frequency, which acts as a barrier

against a wholesale shift. In general terms, the majority of nouns with pattern

d and variation appear to have

developed either from pattern f´ (often

through pattern d´) or from pattern b (often through pattern f). The evidence of variants in Gorbačevič 2010 often captures the earliest or intermediate

stages of these stress shifts, which, in many cases, have taken place over

several centuries.

With regard to stress pattern d´,

it is notable, first and foremost, for the low number of nouns which belong to

it, and, as such, this potentially makes it a fragile stress type. With only

twelve nouns listed in Fedjanina (1982, 99-100), the expectation is that the

rather anomalous nature of their stress is connected to and maintained by high

frequency, and, indeed, this appears to be the case: eleven of the nouns have

high frequency and only one (дрога́)

low frequency. In addition to this factor, high frequency can logically be

expected to act as a resistance to any change of stress, since familiarity with

this pattern leads to a high degree of stability, including, of course, the

retracted stress of the accusative singular. As a stress type, pattern d´ is able to continue to exist first

and foremost through the high frequency of its members.

In terms of the hypothesis put forward in this article, the main question to be answered is whether pattern d´ is indeed a subtype of or transitional path to pattern d, insofar as nouns of the former pattern are gradually moving towards the latter, and whether frequency plays any role in this. The data from Kiparsky 1962 indicates that all twelve nouns of this pattern probably had pattern f´ at an earlier stage of Russian and, therefore, pattern d´ is the result of a historical transition. However, the question remains about the relationship of pattern d´ to the ascendant pattern d. Seven of the twelve nouns (58.3%), show a tendency either а) away from an older, now archaic pattern d´ towards now normative pattern d (see above (3.2) изба́, коса́ (‘scythe’)), or, b) towards a currently non-normative pattern d (generally indicated by ‘неправильно’ or ‘допустимо’) away from normative pattern d´ (see above земля́, коса́ ‘plait’, коса́ ‘scythe’, спина́, стена́, цена́). There is, therefore, evidence of a shift towards pattern d, but it is not strong, nor does it encompass all nouns of this type. Nevertheless, where there is variation in these nouns, it generally involves the accusative singular, thus indicating that pattern d certainly is the source of most volatility in pattern d´ and can, therefore, be viewed as the next stage in a transitional path from d´ to d which continues to develop. The nouns вода́, дрога́, душа́ and зима́ show no tendency currently to shift the accusative singular stress to the ending; зима́ had ending stress in the accusative singular at an earlier stage (early nineteenth century, especially in poetry), though this appears to have been pattern f, not d. In the case of one noun, река́, stylistic information is not present in Gorbačevič 2010, but an ongoing shift of d´ to d can be assumed.

The results found in this paper essentially coincide with Ukiah’s (2003,

14) who sees levelling of the accusative singular to ending stress in line with

the rest of the singular forms as characteristic, but who also concedes that “a

number of items are nevertheless offering strong resistance to this movement.” They

are also analogous to the same trend in nouns of patterns f and f´, whereby the

latter are moving towards the former by means of moving the retracted stress of

the accusative singular to the ending (see Lagerberg 2018). As nearly all

current variation in pattern d´

indicates pressure from pattern d,

the former can justly be viewed as a sub-type of and transitional path to the

latter. In the coming decades it seems likely that this pressure will increase

and more variation will occur in the accusative singular forms of nouns of

pattern d´ as they move towards a

fixed ending stress in the singular sub-paradigm.

[1]In fact, Fedjanina 1982, and also Kiparsky 1962, use different systems of stress notation (e.g. pattern d is pattern BA in Fedjanina 1982, pattern A in Kiparsky 1962). Only Zaliznjak’s system will be used in this article in order to avoid confusion and needless complexity, i.e. Fedjanina’s and Kiparsky’s systems are adapted to Zaliznjak’s.

[2]In this article we use the generally adopted alphabetical system of Russian stress patterns found, for example, in Zaliznjak (2010). There follows a list of the stress patterns relevant to the present discussion (mobile stress types are marked in bold):

a: fixed stem stress (e.g. кни́га)

b: fixed desinential stress (e.g. праща́)

d: desinential stress in the singular, stem stress in the plural (e.g. жена́)

f: desinential stress throughout, except for the nominative plural which has stem stress on the initial stem syllable (e.g. губа́)

d´: as pattern d above, but with stress retracted

on to the initial stem syllable in the accusative singular (e.g. спина́)

f´: as pattern f above, but with stress retracted

on to the initial stem syllable in the accusative singular (e.g. голова́)

[3]Gorbačevič (1978a, 53) characterises the important difference between oral and written stress

variance in the following way: ‘Ударение ‒ факт устной, звучащей речи. Варьирование

же на этом

уровне не

только свободнее

и шире, но и

менее

доступно для

регламентирующего

воздействия,

чем, скажем,

вариантность

графически

выраженных

морфологических

форм.’

[4]A third possibility concerns a complete shift of stress in all forms to either the stem (a pattern) or the ending (b pattern); this possibility, however, plays a minor role in the discussion and does not appear, according to Ukiah’s findings, to be a factor.

[5]See Comrie et. al. 1996, 83.

[6]Cubberley does not

list all five nouns, but the one used as the label for the pattern (борьба

‘struggle’) does not generally

occur in the plural, thus making the pattern b label in at least one case entirely theoretical, and, therefore,

rarer still.

[7] Общий

частотный словарь

лемм для современных

(>1950) текстов текущей

версии НКРЯ at: http://corpus.leeds.ac.uk/serge/frqlist/. See also Sharoff (2005) for more background

on this data.

[8]Homonyms

with different stress positions are not considered variations as such; thus, Gorbačevič 2010 gives басма́

‘seal’ vs. ба́смa ‘brown hair dye’.

[9]Different

stress positions in the initial form of nouns which subsequently gives rise to

two different stress paradigms (of which one is fixed stem stress) are also not

included here as variants; thus, Gorbačevič 2010

gives быстрина́