ISSN: 2158-7051

====================

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

RUSSIAN STUDIES

====================

ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/1 )

|

ISSN: 2158-7051 ==================== INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES ==================== ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/1 ) |

An Examination of Contemporary Use of the Traditional Nomadic Infant Cradle board (beshik) Among the Kyrgyz of Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Jake Zawlacki *, Matthew Derrick **

Summary

The

Kyrgyz beshik is a Central Asian

traditional cradle board similar in structure and purpose to cradle boards

found in other formerly nomadic cultures. This form of swaddling is a premodern

practice that has well documented risks, the most notable being developmental dysplasia

of the hip. Its usage in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, has largely been

undocumented. We collected survey data of local participants to understand which

Kyrgyz are most likely to use the beshik.

Most of our findings were consistent with modernization theory in that

increased levels of education, urbanization, and degrees of Russification of a

household all had inverse relationships with likeliness of beshik usage. Participants with parents from the southern provinces

of Kyrgyzstan are significantly more likely to use the beshik than those with parents from the northern provinces. Key Words: Swaddling, traditional medical practices, cradle board, Kyrgyz, Kyrgyzstan. Introduction The Central Asian cradle board, known in

Kyrgyz as the beshik, is a

traditional nomadic infant cradle that historically has been used throughout

Central Asia, including the post-Soviet countries Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, as well as among Central Asian

minority populations in Iran, Mongolia, Turkey, and Afghanistan (Turkestantravel

2018). The beshik is most useful

within its original nomadic context, as observed among other nomadic cultures

such as the Sami of northern Scandinavia and the Navajo and Apache Native

American tribes (Melbin 1962: 62-66). By immobilizing the arms and legs and

binding them straight against the cradle board, the beshik protects the infant from the dangers that come with nomadic

settings, such as exposure to animals, open fires, and treacherous terrain. The

beshik offers an additional benefit

of providing security and comfort within this tightened form of swaddling. A

study of irritability in infants indicates that swaddling infants often

exhibits favorable results regarding sleep, crying, and overall irritability

(Lipton et al. 1964: 562). The beshik

is also a cost-effective alternative to diapers while maintaining a basis of

cleanliness for the infant. There are, however,

risks that have been found among traditionally nomadic cultures that use cradle

boards of similar design. Plagiocephaly, the flattening of the head, and developmental

dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a congenital hip disorder referring to an

abnormality of the pelvis in relation to the femoral head and complete

congenital hip dislocation, have all been linked to traditional swaddling

techniques similar to the Kyrgyz cradle board (Loder & Skopelja 2011; Blatt

2015). Infants with scoliosis also had a tenfold increased rate of DDH compared

to those without (Hooper 1980: 449). While plagiocephaly is mostly benign in

its consequences, DDH often results in a lifelong physical disability lacking a

noninvasive solution. Kyrgyzstan’s

current medical system makes it difficult to gather data on the specifics of each

type of disability. This is especially the case when a shortened leg or

a mild limp is perceived as socially and culturally acceptable and even normal,

as seen in Navajo populations (Rabin et al. 1966: 43). Western researchers understand

DDH as a disease (Rabin et al. 1966), and it furthermore accounts for a large

portion of physical disabilities in Kyrgyzstan; however, that portion cannot be

determined under the current medical system’s analysis and discernment of

physical disabilities. Loder and Skopelja’s analysis of DDH in over four

hundred peer-reviewed articles indicates that the continued use of improper

swaddling techniques, such as straight-legged swaddling present in the beshik, contributes a significant risk

factor in the development of the disease (Loder & Skopelja 2011: 23). The

evidence presents itself in various studies including Navajo, Apache, and Sami

nomadic populations. Past research indicates proper swaddling techniques will

not only reduce the risk factors for DDH, but also provide the same benefits as

the Kyrgyz beshik (Ishida 1993). Against the foregoing, in

this paper we address the guiding following questions: How prevalent is the use

of the beshik in Kyrgyzstan? Which

segments of the population are more likely to utilize the device on their

children? And why might people in Kyrgyzstan, and more broadly Central Asia, in

the face of contemporary medical evidence suggesting risks involved with using

the beshik, continue to use the

traditional cradle board long after abandoning the nomadic lifestyle for which the

beshik was intended. We investigate

these questions through analysis of data we collected through original social surveys

conducted during the fall and winter of 2017 in Bishkek, the capital and

primate city of Kyrgyzstan. Our null hypothesis is as follows: The likelihood

of the contemporary Kyrgyz to use the beshik

positively correlates to the proximity

to traditional nomadism. In proximity we

first speak in temporal terms, ‘traditional’ counterposed to ‘modern’ or ‘modernized’.

However, our utilization of proximity is also employed on a spatial axis, as

certain geographic areas—specifically, the northern part of Kyrgyzstan, part of

the great Eurasian steppe—are more historically associated with nomadism than

other geographic areas, i.e. the south of Kyrgyzstan, site to Osh and

historical settlements of the Ferghana Valley. To test our null hypothesis, we

examine the correlation between four different independent variables—home

language, education level, parents’ birth region, and length of time in

Bishkek—and inclination to use the beshik. Background The sovereign Republic of Kyrgyzstan is located

in Central Asia and shares borders between Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, China, and

Kazakhstan. It is a landlocked country with roughly 6 million inhabitants, two-thirds

who live in rural areas (Kyrgyz Republic 2013); another 1 million live in the

capital city Bishkek, the main destination of rapid post-Soviet migration and urbanization

within the country. Contemporary Kyrgyzstan combines historical nomadism,

Russian cultural influences, and contemporary Western influences. In the mid-nineteenth

century, the area that currently comprises contemporary Kyrgyzstan was

incorporated into the Russian Empire and in 1924 became part of the Soviet

Union (Asankanov et al. 2016; Osmonov 2017). The Kyrgyz, who natively speak a

Kipchak Turkic language (closely related to Kazakh and Tatar), moved from a

historically nomadic way of life to a sedentary lifestyle through agriculture

and urbanization over the past two hundred years (Boyanin 2011). This relatively

recent break from nomadism has left some persistent cultural traditions in its

wake. The beshik is an example of

this persistence. Central Asia is generally

considered to consist of the five post-Soviet countries that end in –stan:

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. For the purposes

of this study, however, Central Asia refers to an area that encompasses the Turkic-speaking,

Muslim-majority ethnic groups that currently reside in the five post-Soviet Central

Asian states, and the pockets of minorities that cross over into other political

borders.[1]

Today in Kyrgyzstan large numbers of people continue to use the beshik much in the manner their ancestors had in prior centuries (see Figure 1). Many of the inhabitants of the previously listed countries of Central Asia, however, no longer use the beshik. With little research done on the topic, it is difficult to identify which parts of Central Asia the beshik is being actively used, or where it is seen as a tradition with little real-world application. This distinction is apparent in numerous tourism websites where the beshik is most often referred to in conjunction with the beshik toi, a celebration usually occurring forty days after the birth of the child serving a similar function as a Western baby shower (turkestantravel 2018). A tourism website in Uzbekistan, for example, places strong emphasis on tradition with little emphasis on its functionality or practicality:

This ancient ceremony has been preserved in Uzbekistan culture from times [sic] immemorial and still is one of the most popular holidays in Uzbekistan. For every family it is a great holiday. All relatives, neighbors and family friends are involved in the preparation to the beshik-tui. It is celebrated on the fortieth day after birthday of a child. Relatives of the young mother bring ‘beshik’, a beautifully embollished [sic] cradle, clothes, and everything necessary for a newborn. Also it is a custom to bring bread, sweets and toys, wrapped in clothes. Traditionally, while guests enjoy and regaling themselves at the holiday table, in the nursery elder women carry on the rite of first swaddling and placing the child into the ‘beshik’. The ceremony finishes with a presentation of a child, during which invited guests present the child with gifts. (Advantour 2018)

The inclusion of the beshik in Uzbekistan tour websites shows the self-observed importance of the tradition to Uzbek culture. This tradition, while found in Kazakh and Kyrgyz populations as well (RFERL 2015), is more of a nod to traditional practices than it is an implementation of traditional practices in modern settings.

The beshik’s construction includes multiple components. The frame is made of wood and often painted or embellished with traditional designs. The floor of the beshik features an opening to hold a receptacle for excrement. Depending on the sex of the infant, a chechek, a Kyrgyz type of flute for urine, is placed between the legs of the infant. The infant is wrapped in cloth and bundled with the legs and arms straight against the body. Oftentimes the beshik will also be covered with a type of hood to ensure a dark sleeping environment for the infant. Most Kyrgyz beshiks are built to be low to the ground however there are examples found in Kazakh populations that have longer legs standing higher above the ground.

It is important to note here the synonymous nature of ‘swaddling’ and the use of the beshik in Kyrgyz populations. The two ideas are interlinked because, as of yet, there exists no alternative in the public eye of long-term swaddling without the use of the beshik. There is evidence of mothers swaddling their children outside of the beshik, generally under conditions of transportation, but in the eyes of the public using the beshik undoubtedly means swaddling and swaddling means using the beshik. Our survey data are clear in pointing out the lack of alternative swaddling techniques in the minds of the public. Operating under this assumption, not only the comparison between other cradle boards can be made, but also of other swaddling practices as well. There was not a single survey participant who mentioned swaddling their child outside of a beshik.

The beshik itself is a long-held tradition that predates conceptions of modern Central Asian ethno-national groups (Advantour 2018). The wooden structure and frame are prone to rapid degradation, making an archaeological account of the prior claim impossible. The beshik has remained in use over the centuries because of beneficial reasons, many of which are largely forgotten by cultural groups who have used or continue to use the device. As seen in numerous Native American tribes and the Sami people, having children immobilized provides many advantages in a nomadic lifestyle (Rabin et al. 1966). Basic advantages in a traditional nomadic home might include safety from domestic animals, open fires, and ease of transportation. The beshik is not only a product of nomadism but generally of nomadism in colder temperatures. (Loder & Shafer 2014). An exception to this theory is the circumpolar Inuit populations, where the infant is not bound to a cradle board but is instead carried beneath a hood inside of the mother’s coats, leaving the legs spread around the body of the mother (Erikkson et al. 1980). A comparison of both Sami and Inuit populations, the former using a traditional cradle board, indicates a marked difference in the occurrence of DDH: There was an occurrence of 24.6 of 1000 in the Sami population compared to a lower rate comparable to Caucasians for the Inuit populations (SAAM 2001; Melbin 1962: 62-66). Evidence of an increased risk of DDH is also found when comparing Africans and Native Americans. Native American groups that used cradle boards had a much higher risk of DDH than ethnic Africans (Loder & Skopelja, 2011). The explanation for a lower occurrence of DDH in ethnic Africans is due to the way infants are carried on the backs of mothers with the legs splayed open. This differs from the straight-legged swaddling of the beshik, which does not allow for hip mobility and thus increases the risk of DDH. Climate also plays an important role in whether a cultural group adopts warm swaddling practices as well as cradle boards (Loder & Shafer 2014).

Further benefits of the beshik can be found in a cursory assessment. It provides warmth, security, pressure, and a dark environment for the sleeping infant, who sometimes remain in the beshik for up to eight hours a day for up to two years. Key benefits also include the ability to rock the infant, breastfeed the infant while in the beshik, and freeing up time for the mother, the latter being a common reason found in the interviewed population.

Drawbacks of the beshik also exist in contemporary usage. The most publicly aware side effect accompanied with the beshik is plagiocephaly, the malformation of the cranium generally resulting in a flattened back of the head. This results from the infant being positioned face up in the beshik for a long duration of time during developmental stages. Medical research on plagiocephaly is limited, with no substantial findings indicating that it hinders brain development in any way. Studies of DDH in infants who were swaddled in a form of cradle board, as previously mentioned before, have provided evidence that the forced straightening of an infant’s legs increases the risk of DDH (Loder & Skopelja 2011: 23). This, as our interviews revealed, is largely unrecognized by the public and more commonly referred to as aksap basat roughly translating to ‘a walking limp’, which would refer to individuals with a complete dislocation of the femoral head from the hip socket resulting in a dramatic rocking gait. The more common reference to people with DDH is having one leg shorter than the other. A shortened leg can be attributed to many factors such as nutritional deficiency, trauma, or pelvic tilt but also includes DDH (AAOS 2018). If the femoral head is partially dislocated from the pelvis, one leg will be functionally shorter than the other because of the different heights of the femur. It is also possible that the pelvis will tilt to compensate for this discrepancy which would increase the risk of spine related complications. While these issues are routinely checked for and addressed at early stages in Western medical practices, our fieldwork suggests that they are largely unknown among those who use the beshik in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

Literature

Review

Little literature exists on the topic of DDH in Central Asia. To a significant degree, this the result of a combination of infrastructural problems and data collection methods. The first difficulty in analyzing DDH among the Kyrgyz population is the lack of awareness of the disease itself. Our survey results also indicate follow-up consultations with the child with no mention of proper swaddling techniques. This lack of awareness on the part of healthcare providers mirrors a lack of discretion between different types of physical disabilities as seen in the US State Department’s analysis as well as the Kyrgyz Ministry of Health reports (Kyrgyz Republic 2013). Determining the rate of DDH or congenital dislocation is not possible given the lack of analysis and reporting of these diseases. Another reason DDH and dislocation are not well understood in Kyrgyzstan is because of the varying cultural definitions of physical disability.

As seen in a study of Navajo populations, the definition of physical disability varied among urban and rural groups (Rabin et al. 1965). DDH and the more severe hip dislocation was not seen as a disability among the rural populations because it was not an impediment to bearing children, walking, horse riding, or other routine tasks and was therefore not considered a disease needing correction. A similar claim can be made of Kyrgyz populations who regard a leg significantly shorter than the other as a common issue that can be solved with altered footwear. Rabin’s insight provides a partial explanation to why this disability has not been fully investigated in Kyrgyzstan.

Swaddling has been linked to DDH and congenital hip dislocation for centuries. The practice of straight-legged swaddling has largely fell out of Western culture during the past two centuries and has subsequently been a non-issue for inhabitants of Europe and North America. The early debate of whether to swaddle children in Western culture is observed in Jean Jacques Rousseau’s analysis in Emile:

It is maintained that unswaddled infants would assume faulty positions

and make movements which might injure the proper development of their limbs. That is one of the empty arguments of our false wisdom which has never been confirmed by experience. Out of all the crowds of children who grow up with the full use of their limbs among nations wiser than ourselves, you never find one who hurts himself or maims himself; their movements are too feeble to be dangerous, and when they assume an injurious position, pain warns them to change it. (Rousseau 1767: 11)

Rousseau asserts that liberated children belong to ‘nations wiser than ourselves’ to state philosophical repercussions as well as physical. Since the time of Rousseau, the tradition of swaddling fell out of common practice in Western Europe, which can attribute to the decreased rate of DDH in Caucasians compared to populations that still use straight-legged swaddling techniques (Loder & Skopelja 2011: 28).

A reduced rate of DDH was achieved in Japan after a national campaign to alter traditional swaddling techniques succeeded in targeting congenital hip dislocation (Ishida 1977). The campaign was a response to the straight-legged swaddling technique found in the traditional Japanese cradle basket that has obvious similarities to the Central Asian beshik. Native American populations have also found a decrease in DDH and congenital dislocation of the hip which may be attributed to the disappearance of the tradition as well as the inclusion of diapers inside the cradle, thus mobilizing the hips to some degree as hypothesized by Rabin et al. (1965). This could be a possible route for Kyrgyz and other groups still using similar practices.

The use of the beshik among Central Asian cultural groups is comparable to swaddling because there are no current alternatives to the cradle board. Either someone uses the beshik or does not swaddle at all. With this assumption, we can compare attitudes from other cultures that swaddle their children. Reasons for swaddling infants include comfort, warmth, stability, as well as giving the mother free time to accomplish other tasks (Lipton et al. 1965).

A component of swaddling for which there is no measure in Kyrgyzstan’s current medical system is sudden infant death incident (SUDI), which includes sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) as well as other fatal sleeping accidents. In an analysis conducted in Australia to determine the impact of climate on SUDI, researchers found there to be an exceptionally increased rate of SUDI when the infant was born in the summer months, making climate the most significant factor in determining the risk of SUDI (Beal & Porter 1991: 278). The proposed reason for this being infants born in summer months had a higher risk of SUDI because of the extra cloth and bedding the infant slept with during the winter. Swaddling in a supine position is not a common practice in Australia and was recommended as a possible solution to decrease the risk of SUDI. Numerous studies have shown the supine position to be beneficial in preventing SUDI and is currently recommended as the preferred practice for mothers (Task Force 2016). Climate also impacts the rate of swaddling and therefore an increased rate of DDH (Loder & Shafer 2014: 11). A comprehensive literature review of seasonal variation in DDH indicated that 80 per cent of DDH cases occurred in colder months in both northern and southern hemispheres. While there is significant evidence in support of the winter clothing hypothesis, there also existed spikes in DDH occurrence in spring and summer which refutes the hypothesis to a degree (Loder & Shafer 2014). More research needs to be done to establish stronger correlations between climate and season of birth and the rate of DDH. Swaddling in the supine position therefore provides a range of benefits when executed properly, and considerable disadvantages, sometimes fatal, if executed improperly.

In more recent studies, the practice of swaddling has been linked to cases of hyperthermia, especially when the infant’s head is covered, as well as a higher incidence of respiratory infections in warm homes (Short 1998; Beal & Porter 1991). This was found to be true in an unfortunate fatality resulting from hyperthermia (van Gestel et al. 2002). The case involves a Roma family living in the Netherlands with twins. Under advice from the grandmother to reduce irritability in the granddaughter, the mother began swaddling both children in traditional form. This led to hyperthermic conditions that resulted in the death of one of the children. Van Gestel et al. (2002) speculate on the role of tradition and parental influence in this specific case of swaddling:

It is likely that social and ethnical circumstances of the parents played an important role in the described cases. Respect for older people and the adherence to traditional habits in combination with the inexperience of the mother created the circumstances for the dramatic course. The grandmother’s advice to swaddle the children and keep them in a well-heated room may have been good advice traditionally. Nowadays, however, the circumstances in which the Roma live are different from the past: their mobile homes are well-insulated, all have central heating, and winters in the Netherlands are moderate compared with winters in the Balkan area. This requires additional measures when a child is swaddled, such as regular checks of rectal temperature and supplemental fluids for the child. (van Gestel 2002: 2)

It is important to note the similarities in environmental changes between Roma and Kyrgyz populations. Only with recent changes in housing structures have Kyrgyz moved away from traditional types of housing to more Russian and Western-style houses (Boyanin 2011). This results in a warmer household that may induce similar risks when coupled with traditional practices meant for historically different living conditions. The documentation for specific causes of death in infants in Kyrgyzstan is limited (Kyrgyz Republic 2013). Without proper documentation of clearly identifiable symptoms of swaddling practices such as DDH and plagiocephaly, the health care system in Kyrgyzstan may be decades away from determining increased rates of hyperthermia or respiratory infections in infants.

A study in Turkey investigating mothers and the likelihood of swaddling their children based on certain variables found a decrease in swaddling as the level of maternal education and socio-economic status increased among participants (Yilmaz 2012). The most common reason for swaddling among participants was cited as ‘That’s what I learned from my elders’, at 38 percent of the surveyed population (Yilmaz 2012: 132). Tradition is found to be a common motivator for this practice as found among Turkish, Navajo, and Roma. As we found in our surveys, the same is true for the surveyed Kyrgyz populations, who answered tradition to be the most common factor in deciding to use the beshik with their child.

Methodology

This article draws on data derived from an original social survey designed to gauge demographics, public attitudes, and household practices vis-à-vis the beshik. A total of 219 surveys were conducted with the help of locally trained research assistants. All participants in this study were surveyed in public areas in Bishkek, the capital and primate city of Kyrgyzstan. The areas were chosen because of the heavy pedestrian traffic, helping to assure a significant degree of randomness in sampling. All adults were included in the sampling frame with no preference given to gender, age, or any other demographic.

The survey requested demographic information specific to the years and generations of moving to Bishkek, the number of people and children in the household, highest level of education in the household, conversational language in household, household income, age, religion, gender, and type of housing. The number of years and generations in living in Bishkek indicate the level of urbanization of the family. The number of people and children living in the household are taken as potential indicators of class, development, and/or the closeness of the family unit, as well as the possible influence of family members on the usage of the beshik. The highest level of education and language spoken regularly in the household was surveyed as additional measures of class- and cultural-based affinity. Income, age, religion, gender, and housing were asked to provide foundational demographics and find correlations that may be attributed to these differences.

The survey also included specific questions regarding the Kyrgyz beshik, including household beshik ownership, use with a child, duration of usage, medical doctor’s consultation, and the doctor’s subsequent recommendation in favor of or against the use of the beshik. Ownership was determined by whether a beshik was in the residence. The usage of the beshik was a prerequisite question for follow-up information. If participants did not have children, they were asked if the beshik would be used in the future. The duration of months the beshik was used was gathered to determine an estimated length of time Kyrgyz people use the beshik with their children. Participants were also asked if a medical practitioner had ever consulted them regarding swaddling or the beshik. If participants had been consulted, they then asked if the medical practitioner had given advice for or against the use of the beshik. This was to determine the content and consistency of medical advice.

In addition to quantitative survey data, our research is informed by semi-structured interviews with a sub-sample as well as participant observation and informal discussions that took place while carrying out the interviews.

Results

The use of the beshik remains widespread among the surveyed Kyrgyz. Of those surveyed, two-thirds (147 of 219) had used or intended to use the traditional Central Asian cradle board on their children. To discern which sectors of this population are more likely to employ the beshik, we deploy analysis against the following null hypothesis: The likelihood of contemporary Kyrgyz to use the beshik positively correlates to the proximity to traditional nomadism. We address two aspects of proximity: temporal and geographic.

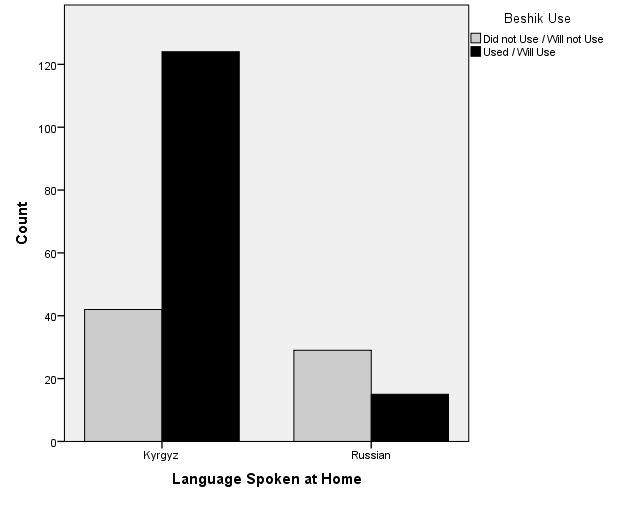

To address the temporal aspect of proximity, understood in basic scholarly terms of ‘traditional’ counterposed to ‘modern’ or ‘modernized’ (Giddens 1991; 1994), we first examine the correlation between home language—Kyrgyz versus Russian—and use of beshik. Here we understand linguistic Russification as a proxy for Europeanisation, a temporal indicator of assimilation to non-traditional cultural influences and, correspondingly, greater distance away from traditional nomadism; conversely, we understand the maintenance of Kyrgyz as the primary home language as an indicator of greater traditionalism. Indeed, as seen in Figure 2, there is strong correlation between language used at home and preference for the beshik. Kyrgyz is spoken in just over three-fourths of all households surveyed; one-fifth of those surveyed reside in Russophone homes (about 4 per cent of the respondents did not indicate which language is spoken at home). A large majority—about 75 per cent—of respondents from Kyrgyz-speaking households choose or would choose to utilize the traditional cradle board; among those in Russian-speaking households, approximately two-thirds of those surveyed indicted opposition to using the beshik. Thus, taking home language as an indicator of degree of traditionalism, there is firm initial support for the null hypothesis.

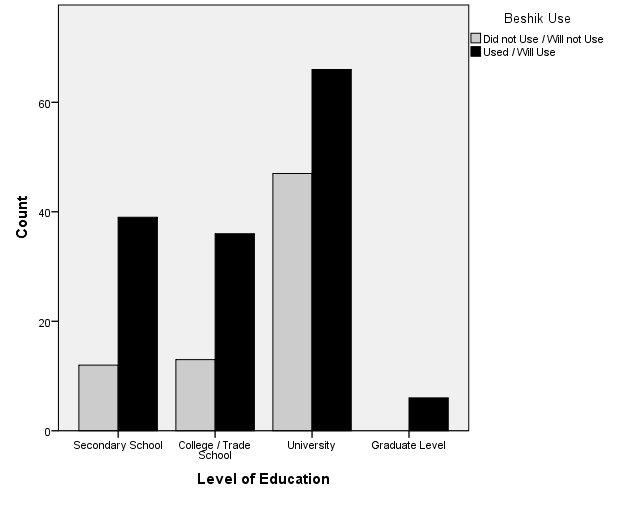

As a second measure of the temporal aspect of proximity, we investigate the relationship between beshik use/non-use and level of education. Here we take education level as a measure of social development, as the concept is generally understood in modernization theory (Chabbott & Ramirez 2000; Inglehart & Welzel 2005); as such, higher levels of formal education correspond to greater distance away from traditionalism. With this measure, again, we find confirming evidence of our null hypothesis. As seen in Figure 3, the likelihood of using the beshik inversely relates to level of education, aside from the highest level. Among respondents with only a secondary school education (n=51), 76 per cent choose or would choose to use the beshik; among those with a college- or trade-level education (n=49), the portion in favor falls slightly to 73 per cent; and among respondents with a university degree (n=113), the pro-beshik contingent drops to 58 per cent. While the first three education level categories support the null hypothesis, the highest level, accounting for less than 3 per cent of all respondents, reverses the trend; all respondents (n=6) with a graduate-level education indicated a desire to use the traditional cradle board, which represents an interesting reversal in the tendency.

To summarize thus far, respondents most likely to utilize the beshik come from Kyrgyz-speaking households and have lower levels of education. Those from Russophone homes with higher levels of education are least inclined. These findings, providing support for our null hypothesis, generally are in line with developmentalist modernization theory.

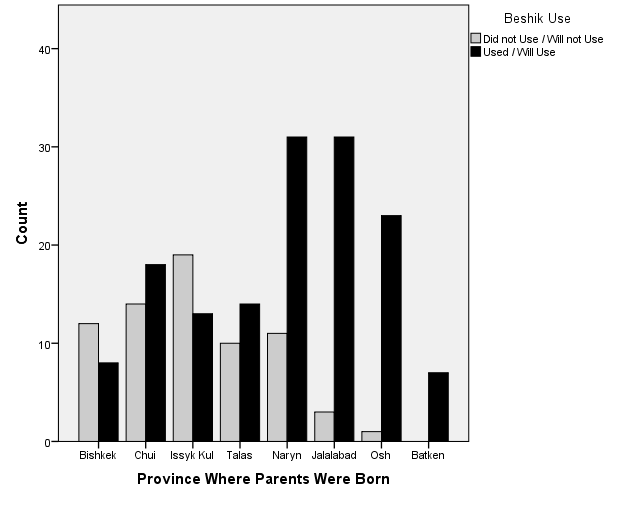

The second axis of proximity is geographic. Based on our null hypothesis that the utilization of the beshik correlates to nearness of geographic spaces where nomadism historically was more prevalent, we test this hypothesis with two questions. First, participants were asked, ‘In which province [of Kyrgyzstan] were your parents born?’ We anticipated that likelihood of using traditional cradle board would be higher in the southern regions than in the northern regions due to differing orientations of cultural influence, i.e. the south is oriented to more traditional cultural influences of the Ferghana Valley, while the north is historically more oriented toward Russia and consequently more impacted by the diffusion of European cultural influences (Asankanov, Brusina & Zhaparov 2016; Osmonov 2017).[2] As seen in Figure 4, a geographic pattern emerges, revealing a north-south split that confirms expectations based on the null hypothesis. Favorability toward the beshik is highly pronounced among respondents whose families hail from the southern regions of Kyrgyzstan: Among respondents with parents from Naryn (n=42), nearly three-quarters report they have used or would use the device; among those with parents from Jalalabad (n=34), 91 per cent respond favorably to the beshik; with parents from Osh (n=24), 96 per cent say yes; and all respondents with parents from Batken (n=7) had used or intended to use the beshik. Compared to the south, attitudes toward the traditional cradle board pronouncedly diverge among respondents whose parents were from northern regions of Kyrgyzstan: Among those with parents from Bishkek (n=20) and as well as those with parents from Issyk Kul (n=32), only 40 per cent are favorably disposed toward the beshik; among respondents with parents from Chui (n=32), 56 per cent express a willingness to use the device; and with parents from Talas (n=24), the favorability level stands at 62.5 per cent.

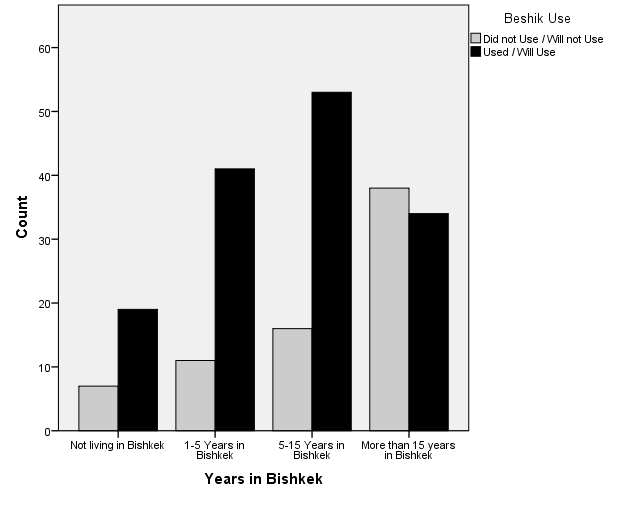

A second geographic variable analyzed is number of years living in Bishkek, which is taken as a measurement of depth of urbanization and sedentariness. As such, this geographic aspect also carries a temporality—we submit that the longer urbanized, in the country’s primate city, should negatively correlate with inclination to utilize the beshik. Indeed, as seen in Figure 5, among those surveyed who have lived in Bishkek for more than fifteen years (n=72) less than half—47 per cent—are favorably disposed toward the traditional cradle board. Among those living in Bishkek for five to fifteen years (n=69), the figure is 77 per cent; and among those who have lived in the capital one to five years (n=52), the portion registers slightly higher at 79 per cent. Among those surveyed who do not live permanently reside in Bishkek (n=26), assumed to be itinerant labor migrants (Abazov 1999), 73 per cent have used or would use the beshik.

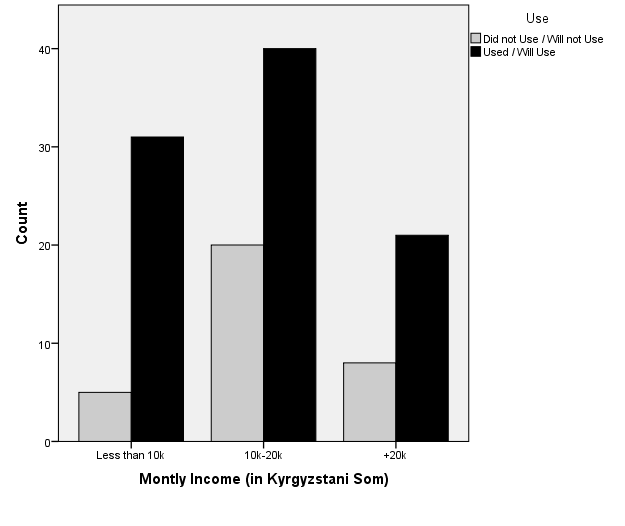

To summarize on the geographic aspect of proximity, the likelihood of beshik usage is most pronounced among Kyrgyz with kin ties based in the country’s south and whose urbanization is most recent. Underpinning this geography are dominant patterns of internal migration in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: from rural to urban spaces, and from the south to the north (Schmidt & Sagynbekova 2008: 111). As is the case with most instances of human migration in the industrial era, the main driver behind Kyrgyzstan’s internal migration is economic opportunity (Abazov 1999). A significant portion of our respondents whose parents hail from southern regions of the country are likely representative of economic migrants, having moved to Bishkek—Kyrgyzstan’s most economically dynamic city—for improved labor opportunities. It follows that this population—in our sample most likely to employ the beshik in rearing children—would be of lower economic status. Indeed, when examining income levels (see Figure 6), an economic class divide is evident vis-à-vis attitudes toward the beshik. Among those reporting a household monthly income less than 10,000 Kyrgyzstani som (about 145 US dollars), 86.5 per cent are favorably inclined toward employing the traditional cradle board; those with household monthly incomes between 10,000 and 20,000 Kyrgyzstani som, the figure drops to 67 per cent; and, in households with monthly incomes greater than 20,000 Kyrgyzstani som, the number stands at 72 per cent.

Conclusion

The fundamental purpose of this research was to discern which sectors of the Kyrgyz of Kyrgyzstan are, a century after their settlement and abandonment of nomadism, more or less likely to use the beshik as a swaddling technique in rearing their infants. To provide answers, we conducted a sample of more than two hundred residents of Bishkek, analyzed their attitudes and habits vis-à-vis the nomadic cradle board, and focused on four questions designed to gauge the proximity to traditional nomadism. We found that, while contemporary overall employment of the beshik remains high among the Kyrgyz of Bishkek, favorability toward usage of the traditional cradle board is uneven among sectors of the population. Those most likely to use the beshik speak Kyrgyz in their household, have lower levels of education, have kin ties to the more traditional regions of south Kyrgyzstan, and settled in Bishkek most recently. On the other hand, Kyrgyz from Russophone households, with higher levels of education, whose parents hail from the country’s north, and have been longest established in Bishkek are least likely to use the device. Furthermore, the decision to utilize the beshik is informed by economic status: The traditional cradle board is most frequently used in households with lowest monthly incomes.

These findings, in providing some basic demographic contours, largely resonate with longstanding modernisation theory found in the social sciences (Giddens 1991; 1994).

In developing a basic profile of which sectors of the Kyrgyz more or less likely to use the beshik, this paper points out the need for additional research on the topic. Whereas we draw on our original quantitative survey data to provide insight into who might employ the traditional infant cradle board, future work will investigate motivations underpinning use of the beshik. This research project hopefully would inform the activities of health professionals, policymakers, and health-oriented nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) who are active in Kyrgyz and other parts of the world where similar traditional cradle boards are commonly used.

[1] See Cowan (2007) for an extended discussion on how the term ‘Central Asia’, along with ‘Middle Asia’, has been variously employed as a geographic region (see also Cowan 2006; Sidaway 2013).

[2] The north and south of the country are dissected by physical barrier of the Tian Shan Mountain Range, contributing to palpable cleavage in the country in terms of culture and politics within Kyrgyzstan (Megoran 2017: 77-133).

Bibliography

Abazov, R. 1999. Economic migration in post-Soviet Central Asia: The case of Kyrgyzstan. Post-Communist Economies 11(2): 237-252.

Advantour. 2018. Beshik-Tui:https://www.advantour.com/uzbekistan/traditions/beshik-tui.htm

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). 2018. Developmental dislocation (dysplasia) of the hip (DDH). OrthoInfo: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/developmental-dislocation-dysplasia-of-the-hip-ddh

Asankanov, A.A., O.I. Brusina & A.Z. Zhaparov (eds.). 2016. Kyrgyzy. Moscow: Nauka.

Beal, S. & C. Porter. 1991. Sudden infant death syndrome related to climate. Acta Paediatrica 80(3): 278-287.

Blatt, S.H. 2015. To swaddle, or not to swaddle? Paleoepidemiology of developmental dysplasia of the hip and the swaddling dilemma among the indigenous populations of North America. American Journal of Human Biology 27(1): 116-128.

Boyanin, Y. 2011. The Kyrgyz of Naryn in the early Soviet period: A study examining settlement, collectivisation and dekulakisation on the basis of oral evidence. Inner Asia 13(2): 279-296.

Chabbott, C. & F.O. Ramirez. 2000. Development and education, in M.T. Hallinan (ed.), Handbook of the Sociology of Education: 163-187. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Cowan, P.J. 2006. Middle Asia versus Central Asia in OSME usage. Sandgrouse 28(1): 62-65.

Cowan, P.J. 2007. Geographic usage of the terms Middle Asia and Central Asia. Journal of Arid Environments 69(2): 359-363.

Eriksson, A.W, W. Lehmann & N.E. Simpson. 1980. Genetic studies on circumpolar populations, in F.A. Milan (ed.), The Human Biology of Circumpolar Populations: 81-168. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Getz, B. 1955. The hip joint in Lapps and its bearing on the problem of congenital dislocation. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 18(1): 1-81.

Giddens, A. 1991. The Consequences of Modernity. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Giddens, A. 1994. Living in a post-traditional society, in U. Beck, A. Giddens & S. Lash (eds.), Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order: 56-109. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Holck, P.

1991. The occurrence of hip joint dislocation in early Lappic populations of

Norway. International

Journal of Osteoarchaeology 1: 199-202.

Hooper, G. 1980. Congenital dislocation of the hip in infantile scoliosis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 67(4): 447-449.

Inglehart, R. & C. Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ishida, K. 1993. Prevention of the onset of congenital dislocation of the hip, in M. Ando (ed.), Prevention of Congenital Dislocation of the Hip in Infants: Experience and Results in Japan: 1-10. Asahikawa: Yamada Company Limited.

Kyrgyz Republic, National Statistical

Committee of Kyrgyz Republic. 2013. Kyrgyz

Republic Demographic and Health Survey. Bishkek: Measure DHS.

Lipton, E.L., A. Steinschneider & J.B. Richmond. 1965. Swaddling, a child care practice: Historical, cultural and experimental observations. Pediatrics 35(3): 519-567.

Loder, R. T. & C. Shafer. 2014. Seasonal variation in children with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics 8(1): 11-22.

Loder, R.T. & E.N. Skopelja. 2011. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthopedics 2011: 1-46.

Mahan, S.T. & J.R. Kasser. 2008. Does swaddling influence developmental dysplasia of the hip? Pediatrics 121(1): 177-178.

Megoran, Nick. 2017. Nationalism in Central Asia: A Biography of the Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan Border. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Mellbin, T. 1962. The children of Swedish nomad Lapps. VII. Congenital malformations. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 131: 62-66.

Osmonov, O. Dzh. 2017. Istoriia Kygyzstana (s drevneishikh vremen do nashikh dnei). Bishkek: Mezgil.

Rabin, D., C. Barnett, W. Arnold, R.H. Freiberger & G. Brooks. 1965. Untreated congenital hip disease: A study of the epidemiology, natural history, and social untreated congenital hip disease. American Journal of Public Health 55(2): 1-45.

Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty (RFERL). 2015. Ethnic Kazakh villagers celebrate a besik toi. 15 September: https://www.rferl.org/a/uzbekistan_kazakh_besik_toi/27234899.html

Reeves, M. 2014. Border Work: Spatial Lives of the State in Rural Central Asia. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

Rousseau, J.J. 2005. Emile. Translation by Barbara Foxley. Public Domain in USA.

Salter, R.B. 1968. Etiology, pathogenesis and possible prevention of congenital dislocation of the hip. Canadian Medical Association Journal 98(20): 933-945.

Schmidt, M. & L. Sagynbekova. 2008. Migration past and present: Changing patterns in Kyrgyzstan. Central Asian Survey 27(2): 111-127.

Sharygin, E. & M. Guillot. 2013. Ethnicity, russification and excess mortality in Kazakhstan. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 11: 219-246.

Short, M. 1998. A comparison of temperature in VLBW infants swaddled versus unswaddled in a double-walled incubator in skin control mode. Neonatal Network 17(3): 25-31.

Sidaway, J.D. 2013. Geography, globalization, and the problematic of regional studies. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103(4): 984-1002.

Society for Applied Anthropology in Manitoba (SAAM). 2001. Summary of SAAM presentations. Anthropology in Practice 2001(1):10.

Task Force

on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. 2016. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths:

Updated 2016 recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 138(5): 1-12.

Turkestan Travel. 2018. Beshik Tuyi:http://www.turkestantravel.com/en/beshik-tuyi

van Gestel, J.P.J., M.P. L’Hoir, M. ten Berge, N.J.G. Jansen & F.B. Plötz. 2002. Risks of ancient practices in modern times. Pediatrics 110(6): 1-3.

van Sleuwen, B.E., A.C. Engleberts, M.M. Boere-Boonekamp, W. Kuis, T.W.J. Schulpen & M.P. L’Hoir. 2007. Swaddling: A systematic review. Pediatrics 120(4): 1097-1106.

*Jake Zawlacki - Stanford University, California, USA 734 Bamboo Drive, Sunnyvale, CA 94086 USA email: jazawlacki@gmail.com

**Matthew Derrick - Humboldt State University, California, USA email: mad632@humboldt.edu

© 2010, IJORS - INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES