ISSN: 2158-7051

====================

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

RUSSIAN STUDIES

====================

ISSUE NO. 5 ( 2016/2 )

|

ISSN: 2158-7051 ==================== INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES ==================== ISSUE NO. 5 ( 2016/2 ) |

VITALITY OF THE KYRGYZ LANGUAGE IN BISHKEK

SIARL FERDINAND*, FLORA KOMLOSI**

Summary

During

the first decades after its independence from the USSR, Kyrgyzstan has intended

to make of Kyrgyz a real state language. Since then, a new generation has been

born and raised in the independent Kyrgyz Republic. Their linguistic behaviour

may have a profound effect in the future of Kyrgyz. This study examines the linguistic

situation in Bishkek. A questionnaire given to 125 students aged between 14 and

18 and direct observation in the streets were used to collect data. The

preliminary results of the research show both, an almost total lack of interest

in the state language by the local non-Kyrgyz students and a very weak attitude

towards their national language by the young ethnic-Kyrgyz. It is expected that

these results may help to create realistic and effective language policies to ensure

the future of the Kyrgyz language in Bishkek and consequently in all the country

in a balanced way. Key Words: Kyrgyz, language revival, Russian, bilingualism, Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek. Introduction 1.1.The Kyrgyz Republic

and the City of Bishkek The

Kyrgyz Republic, also called Kyrgyzstan, is an ex-Soviet landlocked country situated

in Central Asia. Three of its four neighbours, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and

Uzbekistan are also ex-Soviet republics while the fourth one is the People’s

Republic of China. Before its independence, the territory which is currently

known as Kyrgyzstan had been a part of the Russian Empire and of the Russian

Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. In 1924, it was established as an

autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR by the Soviet government and twelve

years later, in 1936, Kyrgyzstan became a Soviet Socialist Republic (Kyrgyz

SSR), the highest level of autonomy within the Soviet Union. The Republic

declared its independence on 31 August 1991 after the collapse of the USSR.[1]

The

200,000 km2

country is inhabited by about 5,363,000 people. Most of its inhabitants belong

to the titular ethnicity, Kyrgyz, which accounts for about 71 percent of the

population. The Kyrgyz are a Turkic speaking nation which moved from the land

that is currently called Khakassia in Siberia to the territory of modern

Kyrgyzstan during the centuries previous to the year 1000 AD.[2] There are, however, two main

minorities, Russians, mainly in the north, and Uzbeks in the south, who account

respectively for 8 and 14 percent of the total population of the country. Other

noticeable ethnic and linguistic groups include Dungans, Ukrainians, Uyghurs, Tajiks

and Germans just to mention some of them.[3]

Kyrgyzstan

is one of the poorest countries in Asia. Unemployment and poverty are common

and it is estimated that every year between 300,000 and 500,000 leave for

Russia.[4] Corruption is also widespread in most

fields, from education to the government. Both issues, economy (and

development) and corruption occupy twelve out of seventeen problems pointed out

by the inhabitants of the country in a poll in 2012, unemployment, mentioned by

61 percent of the respondents, being the first one, and corruption, 36 percent

of the answers, the second one.[5]

The capital of the Kyrgyz Republic

is Bishkek, called Frunze during the Soviet period. The city is also the main

nucleus in Kyrgyzstan with a population of 865,000 inhabitants – a 16 percent

of the total population of the country.[6]

Until the independence in 1991, most of Bishkek’s population belonged to

European nationalities, mainly Russians, Germans and Ukrainians. However, the

massive emigration of those groups towards Russia and Germany definitely changed

the composition of Bishkek’s population and nowadays about 66 percent are

Kyrgyz, 23 percent are Russians and the rest belong to different minor groups.

Bishkek is also the industrial, cultural and political motor of the country.

1.2 Languages of Kyrgyzstan

The state

language of Kyrgyzstan, Kyrgyz, is a Turkic language closely related to Kazakh,

Tatar and Bashkir. Other minority languages such as Uzbek and Uyghur, although

Turkic themselves, differ notably from Kyrgyz.[7]

Russian, the interethnic language of the country, is a Slavonic language with

no relation with Kyrgyz (See Table 1). It was first introduced in the area by

explorers during the 18th century. During the Imperial and Soviet

periods, Russian was an official language, used in most domains. There are also

some other languages spoken by thousands of native inhabitants of the small

republic, such as Uzbek, Dungan, Turkish, Persian/Tajik, Uyghur and others.[8]

|

English |

one |

two |

three |

father |

mother |

son |

language |

|

Kyrgyz |

бир (bir) |

эки (eki) |

үч (üch) |

ата (ata) |

эне (ene) |

уул (uul) |

тил (til) |

|

Kazakh |

бір (bir) |

екі (eki) |

үш (üsh) |

әке (äke) |

ана (ana) |

ұл (ül) |

тіл (til) |

|

Uzbek |

bir |

ikki |

uch |

Ota |

ona |

o’g’il |

til |

|

Uyghur |

بىر (bir) |

ئىككى

(ikki) |

ئۈچ

(uch) |

ئاتا (ata) |

ئانا (ana) |

ئوغۇل (oghul) |

تىل (til) |

|

Russian |

один (adin) |

два (dva) |

три (tri) |

отец (atyets) |

мать (mat’) |

сын (syn) |

язык (yazyk) |

|

Ukrainian |

один (odin) |

два (dva) |

три (tri) |

батько (batko) |

мати (mati) |

син (sin) |

мову (movu) |

Table 1: Kyrgyzstan languages

compared to their closest relatives

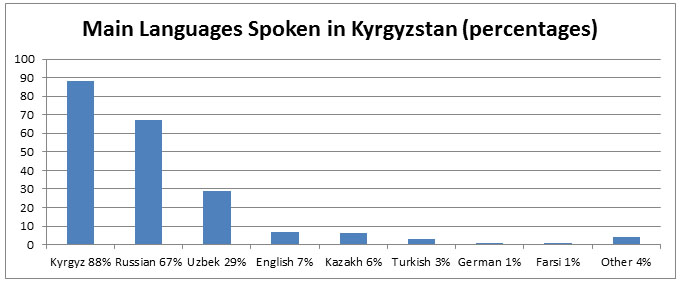

About

88 percent of the people of Kyrgyzstan affirm to be able to speak Kyrgyz and 67

have skills in Russian (see Graph 1).[9]

Unfortunately, the figures mentioned may not only include native, fluent users

of the languages but also people with very limited command of them or even

people who say to speak a language according to their ethnicity instead of

according to their knowledge of the language mentioned.[10]

Graph 1: Main languages spoken in

Kyrgyzstan. The total percentage sums more than 100 because several languages

per person were allowed.

1.3 Historical Language Policy in Kyrgyzstan

1.3.1 The Russian Empire and the USSR

By

the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, a form of Arabic orthography was

employed to write the local [Turkic] dialects in Central Asia, however, the

literacy rates were very low. This written form of those dialects was mainly

employed in religious education.[11] In

order to overcome the problem of illiteracy in the region, the Bolshevik

government tried to adapt the Arabic script into a standardised orthography

which would be more suitable to the Turkic phonetics and would increase

literacy among all the population. The project did not succeed, however, those

inconveniences did not put an end to the efforts to modernise the Turkic

dialects of the Soviet Union. In 1926, a shift to Latin alphabet was proposed and

was finally implemented in 1928.[12]

Interestingly, this very same year, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk established a new successful orthography for Turkish,

the most spoken language of the family, in the same direction, from the Arabic

alphabet to the Latin one.

Until

the beginning of the twentieth century, the Turkic population of Central Asia

did not have any national or even linguistic conscience. Tribalism and the

Islamic religion were the links that joined together social groups. The Soviet

government, then, decided to choose some majority dialects from each language

variety, standardise them, and use them as a base for literary or official

languages.[13] Although some authors suggest

that the Soviet governments were in fact ‘creating new languages’ to divide the

Turkic communities, it is also a fact that it was impossible to choose a single

dialect for all the tribes, since they were not mutually intelligible as proves

the example of the Tatar government officials in Turkestan SSR during the

1920s, who were not understood even by educated Uzbeks.[14]

During

the following decades, the USSR languages suffered some revisions and reforms

in order to make them available to larger population groups, although political

reasons were also involved.[15] One

of the main changes was the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet for all the

languages, except for the few with strong tradition in other alphabets, such as

Armenian and Georgian.[16]

Despite

the criticism by some sources, the standardisation and the reforms carried out

by the Soviet governments increased both, literacy and language prestige of

Kyrgyz. In 1913, before the standardisation, no book was published in Kyrgyz,

while in 1957 over 400 titles were published and 484 in 1980.[17] In 1989, the Soviet Parliament of the

Kyrgyz SSR declared Kyrgyz the state language of the Republic, while Russian

would have the role of interethnic language.[18]

1.3.2 The Kyrgyz Republic

After

the Soviet law which declared Kyrgyz the state language of the Republic and

until the independence in 1991, the language seemed to experience a revival and

it was assigned a central role in nation building and in the preservation of

the Kyrgyz identity.[19] This

fact was among the ones which provoked the migration towards Russia and Germany

of about 145,000 Russian and German speakers, depriving Kyrgyzstan of thousands

of skilled workers and specialists which in turn provoked a severe decline of

the local economy. In order to reverse, or at least attenuate, the situation,

the government of the Kyrgyz Republic declared in 1992 that in certain

locations where Russian speakers constituted the majority of the population,

Russian was allowed to be used in commerce and documents. Moreover, the new

Criminal Code, passed in 1993, includes an article punishing discrimination of individuals

for their ethnicity.[20]

Migration

towards Russia continued and the Kyrgyz government became forced to officially

increment the presence of Russian. Thus, in 1994, Russian became official in

all areas where Russian speakers where majority. Nevertheless, up to 38 percent

of the Russians of Kyrgyzstan continued expressing their wish to leave the

country.[21] In 2000, Russian changed its status

becoming an official language in all the country, while Kyrgyz retained its

status as state language, as stated in Article 10 of the 2010 Kyrgyzstani

Constitution.[22]

Although

the government has understood the need to recognise Russian as a main language

in all the country, the other minority languages do not enjoy the same

conditions, even when, as in the case of Uzbek, there are more native speakers

than native Russian speakers. Uzbek speakers continue seeing their schools

getting closed and their language rights ignored.[23]

1.4 Language education in the Kyrgyz Republic

Kyrgyzstan

has an educational system structured in times of the Soviet Union which has

been partially reformed during the two decades of the history of the Kyrgyz

Republic. The results, however, have not proved to be very successful.

According to the 2010 PISA Report, 80 percent of the Kyrgyz students are under

the minimum level in science, ranking number 57 out of the 57 countries

surveyed.[24]

In

2012, there were 203 Russian schools in all Kyrgyzstan which is about 11

percent of the total schools of the country. Most of the rest of schools also offer

bilingual teaching or Russian as a subject.[25]

Russian schools are highly prestigious and in high demand by Russian parents

and by those from other ethnic groups since students of those schools not only

learn an international language, but also perform much better than their

counterparts in Kyrgyz or Uzbek schools.[26]

Higher education in Kyrgyzstan is available in several languages, including

Kyrgyz, Russian, Uzbek, English, Turkish and a few others.[27]

Between

33 and 50 percent of the time spent in education is devoted to language and

literature which includes Kyrgyz, Russian and a foreign language, usually

English or German (See Table 2). Despite that fact, Kyrgyzstan occupies the

last position in the PISA ranking in reading and only 7 and 1 percent of its

inhabitants declare to know English or German respectively.[28] See also Graph 1.

|

|

1st Grade |

2nd Grade |

3rd Grade |

4th Grade |

5th Grade |

6th Grade |

7th Grade |

8th Grade |

9th Grade |

10th Grade |

11th Grade |

|

Kyrgyz Language |

7 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

3/2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Kyrgyz Literature |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2/3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Russian Language |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

Russian Literature |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Foreign language |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Table 2: Language education in Kyrgyz

medium schools in Kyrgyzstan[29]

Methodology: Survey

and Observation

The

following study has been carried out in two different steps: 1) an initial

survey with students aged between 14 and 18 and 2) by observation of language

behaviour in different locations of the city of Bishkek.

2.1 First step: the survey

2.1.1 Centres

Three

different centres were chosen to carry out this part of the research during

April and May 2015. The first one is a national school, where students learn in

Kyrgyz and in Russian. The ethnic composition of the group fits almost

perfectly with the ethnic composition of Bishkek. The second school is an

English-Russian-Kyrgyz international school managed by a Turkish organisation.

Although most lessons are taught in English, pupils receive education in

Russian and Kyrgyz as well. The number of students with Kyrgyz background is

considerable but they are outnumbered by foreign students, mainly children of

Turkish immigrants. The last school surveyed is an international school which

offers education through the medium of English only. Although most students in

this centre are ethnic Kyrgyz from the upper social classes of Bishkek there is

also a relatively high percentage foreign pupils, mainly from Pakistan. In all

three schools, the rest of the students belong to ex-USSR nationalities such as

Russians (mostly in the national school), as well as Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Uyghurs

and others.

2.1.2 Subjects

Initially,

students of 9th, 10th and 11th grades (students

aged between 14 and 18) of three different schools in Bishkek (See Table 3).

|

|

Ethnic Kyrgyz (at least 1 parent) |

Other ex-USSR nationalities |

Foreigners |

TOTAL |

|

Kyrgyz-Russian National School |

30 (64%) |

17 (36%) |

0 (-) |

47 |

|

English-Kyrgyz/Russian School |

20 (43%) |

5 (11%) |

22 (46%) |

47 |

|

English-medium School |

17 (51%) |

3 (10%) |

11 (39%) |

31 |

|

Total |

67 (54%) |

25 (20%) |

33 (26%) |

125 |

Table 3: Distribution of respondents

by school and nationality

2.1.3 Instruments

The

basic instrument used in this study was a very simple questionnaire designed to

enquire about the basic language use of the students within the family circle.

It included questions about communication between family and parents, between

parents, common language within the family, and language use among siblings

(See Appendix 1). More direct questions such as ‘what is your native

language?’ or ‘what is your family language?’ were avoided due to

the generalised confusion between mother tongue (first language) and ethnic

tongue (the one that they are supposed to speak due to their ethnic origin).

Questions about other domains such as language at school or with friends were

not included since the instruction language differs from school to school and Kyrgyz

is not a universal language spoken by all ethnicities. The document containing

the questionnaire included all the items in both versions, a Russian one

(common language among the ex-USSR people) and an English one (common language

among foreign students).

2.1.4 Procedure

In

some cases, the questionnaires were handed out by the researchers. In other

cases, some local teachers gave them to their students.

2.2 Second step: observation

2.2.1 Location

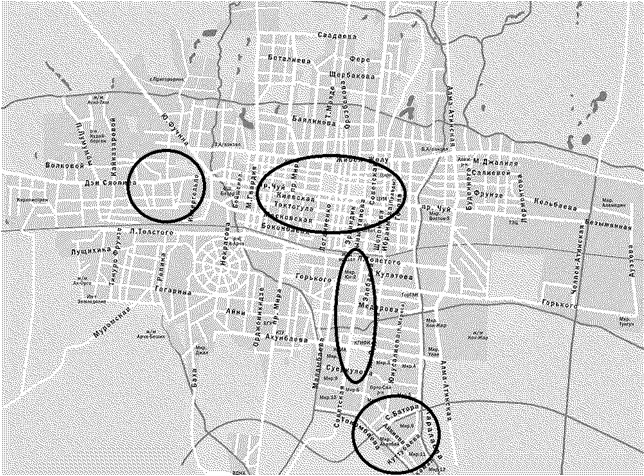

The

Linguistic behaviour of the residents in Bishkek was monitored in various

districts of the city including the wealthy southernmost micro-districts, the

city centre and the north-western districts, which are among the poorest ones

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Areas where the study was carried out.[30]

2.2.2 Procedure

For

the first part of the observation, the researchers took note of the language

displayed in shops and businesses including small food shops, supermarkets,

furniture shops, travel agents, notary publics and beauty salons to mention a

few. It was specified whether the signs were 1) fix, such as a big neon

sign with the name of the business, or 2) temporary, such as public

short notes as ‘back in 5 minutes’, ‘open’, ‘close’, ‘please, call this

number’, etc.

The

second part of the observation, also carried out in different locations of

Bishkek, consisted of taking note of the language in which Kyrgyz-looking

people talked to other Kyrgyz-looking individuals.

2.2.3 Subjects

The

study requested businesses with fix and temporary signing, with the exception

of those situated in the markets, where fix signing is not common. In total, 76

businesses were monitored according to the distribution shown in Table 4.

|

Micro districts |

40 |

|

Market |

7 |

|

Shopping Centre |

6 |

|

City Centre |

22 |

Table 4: Businesses according to its

location

A

total of 20 conversations by Kyrgyz-looking people were identified as Russian

or Kyrgyz. The subjects belonged to all age groups from children to adults,

families and older people.

3 Survey results

3.1 Use of Kyrgyz in families – Language spoken by parents to each

other

Most

of the ethnic Kyrgyz individuals aged 20 and over are either immigrants or

first generation in the city. These immigrants come from all over rural

Kyrgyzstan, where most people function only in Kyrgyz. It is, therefore,

understandable that an overwhelming majority of the parents still use only Kyrgyz

to talk to each other. Evidently, that rate is totally different when one of

the parents is not Kyrgyz, and it is virtually inexistent among ethnic

non-Kyrgyz parents.

|

|

Russian without Kyrgyz |

More Russian than Kyrgyz |

More Kyrgyz than Russian |

Kyrgyz without Russian |

Only other languages |

|

Kyrgyz (both parents) |

21% |

10% |

17% |

52% |

- |

|

Kyrgyz (one parent) |

50% |

- |

12% |

- |

34% |

|

Total Kyrgyz |

24% |

10% |

17% |

45% |

5% |

|

Other USSR nationalities* |

96% |

- |

- |

- |

4% |

|

TOTAL |

41% |

6% |

11% |

31% |

4% |

*It may include the use of Russian

along with the student’s native language

Table 5: Language used by parents to

talk to each other

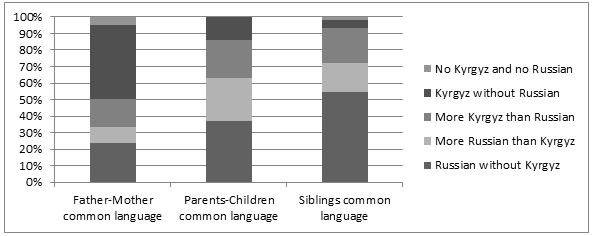

3.2 Use of Kyrgyz in families – Common language spoken between

generations

Despite

being fluent Kyrgyz speakers and users of Kyrgyz in their relationship with

their spouses, most ethnic-Kyrgyz parents settled in Bishkek choose either only

Russian or mainly Russian to talk to their children and only one third maintain

Kyrgyz as their main intergenerational language. It is also interesting to

notice that after more than 20 years of officiality, Kyrgyz has no attraction

for families of any ethnic background since most families choose Russian as the

most adequate linguistic tool to function in the city.

|

|

Russian without Kyrgyz |

More Russian than Kyrgyz |

More Kyrgyz than Russian |

Kyrgyz without Russian |

Only other languages |

|

Kyrgyz (both parents) |

32% |

27% |

24% |

17% |

- |

|

Kyrgyz (one parent) |

64% |

18% |

18% |

- |

- |

|

Total Kyrgyz |

37% |

26% |

23% |

14% |

- |

|

Other USSR nationalities* |

100% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

TOTAL |

55% |

19% |

16% |

10% |

- |

*It may include the use of Russian

along with the student’s native language

Table 6. Common language in families

3.3 Use of Kyrgyz in families – Language spoken by students with

their siblings

About

two thirds of the students regardless their nationality and more than a half of

the Kyrgyz teenagers from Bishkek speak with their siblings in only in Russian

without using any Kyrgyz. Therefore, it must be concluded that Russian is also

the main language employed to chat with friends, to play and other features of

social life.

Although this tendency is clear in

all schools surveyed, there are notable differences among them. Those

differences seem directly related to the language in which students are

educated at school. As a rule, it can be concluded that the less the

influence of Russian is, the slower the shift from Kyrgyz towards Russian seems

to be. Therefore, those who use more Kyrgyz with their siblings are pupils who

study in the English-medium school while those who attend national schools are

more likely to employ Russian with their siblings in a monolingual way.

|

Language spoken→ |

Russian without Kyrgyz |

More Russian than Kyrgyz |

More Kyrgyz than Russian |

Kyrgyz without Russian |

Only other languages |

||||||||||

|

Student’s nationality↓ |

ENG¹ |

EN-LO¹ |

LO¹ |

ENG |

EN LO |

LO |

ENG |

EN LO |

LO |

ENG |

EN LO |

LO |

ENG |

EN LO |

LO |

|

Kyrgyz - both parents |

40 |

47 |

67 |

33 |

11 |

19 |

27 |

37 |

7 |

- |

5 |

7 |

- |

|

|

|

Kyrgyz - one parent |

50 |

100 |

75 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

25 |

- |

- |

- |

50 |

- |

- |

|

Total Kyrgyz by school |

41 |

50 |

68 |

29 |

10 |

16 |

24 |

35 |

10 |

- |

5 |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

|

Total Kyrgyz General |

55 |

18 |

21 |

5 |

2 |

||||||||||

|

Other USSR nationalities² |

66 |

100 |

100 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

33 |

- |

- |

|

TOTAL By school |

47 |

61 |

78 |

26 |

8 |

11 |

21 |

27 |

6 |

- |

4 |

4 |

5 |

- |

- |

|

TOTAL General |

66 |

13 |

15 |

3 |

2 |

||||||||||

Table 7. Language behaviour among

the surveyed students excluding non-ex-Soviet nationals (percentages).

¹ENG: English-medium school; EN-LO:

English/Local-medium school; LO: Local (Kyrgyz/Russian)-medium school

²It may include the use of Russian

along with other native language of the student

The

relation between the language used at school and the language used with

siblings is also evident in the fact that a third of the students of the

English-medium school use some English as an auxiliary language with their

siblings, despite that none of them is an English native speaker (see Table 8).

|

|

English-medium school |

English-Local-medium school |

Local Kyrgyz-Russian school |

|

English Native speakers |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Users of some English with

siblings |

33% |

18% |

2% |

Table 8. Use of English as auxiliary

language among siblings.

Graph 2. General language use among

Kyrgyz inhabitants of Bishkek (at least one ethnic Kyrgyz parent)

4 Observation results

4.1 Language behaviour

by Kyrgyz in informal conversations in the streets of Bishkek

Out

of the 20 conversations among Kyrgyz-looking people heard by the researchers in

different areas of Bishkek, 65 percent of them were in Russian and only 35

percent in Kyrgyz. Most children and youngsters were heard speaking Russian.

The span of time the conversation

ranged from a few seconds to approximately one minute, therefore it is also

possible that the speakers used code switching during the whole conversation,

however this point have not been tested.

4.2 Use of Kyrgyz and Russian in businesses in Bishkek

As

seen on Table 9, the use of Russian-Kyrgyz bilingual fix signing is high in

most areas of Bishkek. There are also many Russian monolingual signs and some

foreign language signs, mainly containing well-known words such as ‘fast-food’,

‘fashion’, ‘pizzeria’, etc. The reason for the strength of Kyrgyz

in this domain can be attributed to official regulations, compelling businesses

to sign in the state language. Since those dispositions do not apply to

temporary signing, such as notes of ‘back in 5 minutes’, ‘open’, ‘close’,

etc, the presence of Kyrgyz becomes minimal. In fact, no Kyrgyz monolingual

sign was spotted. Moreover, all bilingual signs were posters and signs printed

by brands. No Kyrgyz-only or Kyrgyz-Russian handwritten or home printed sign

was discovered, although Russian monolingual notes were common all over the

city.

|

|

Russian |

Bilingual |

Kyrgyz |

Only other |

|

Fix Signs |

||||

|

Micro-districts |

14% |

62% |

8% |

16% |

|

Shopping centres |

43% |

14% |

- |

43% |

|

City centre |

32% |

59% |

- |

9% |

|

Temporary signs |

||||

|

Micro-districts |

84% |

16% |

- |

- |

|

Market |

100% |

- |

- |

- |

|

Shopping centre |

86% |

14% |

- |

- |

|

City centre |

82% |

14% |

- |

5% |

Table 9. Use of languages in

businesses in Bishkek

Conclusion

Kyrgyz

could be considered an endangered language in the city of Bishkek. Although

most parents still use it as their main tool to talk to each other, there is an

endemic tendency not to transmit it to their children, maybe due to the feeling

of superiority of Russian among the Kyrgyz, who consider that language a tool

of international communication and of social progress.[31]

This tendency has compelled many

children and teenagers to learn some Kyrgyz only at school instead of at home.

This fact makes them see the language as a school subject instead of a language

to be used with family, friends, shopping and other daily activities and even

more children and teenagers completely abandon it in behalf of Russian, which

is the only language of 55 percent of the ethnic-Kyrgyz and 66 percent of the

total teenage population (Kyrgyz and other ex-USSR nationalities) of Bishkek.

Outside

the family circle, the situation does not help the language much. As seen, when

there is no legal rule about it, most businesses choose to communicate with

customers in Russian. This voluntary Russian-immersion situation is also

evident in the streets and parks of Bishkek. As discussed previously,

non-Kyrgyz citizens of Kyrgyzstan do not use Kyrgyz to talk to each other, but

even Kyrgyz are losing the habitude of talking their national language not only

with strangers but also with family and friends.

In

most countries, cities and particularly the capital city act as a trend

pioneer. This is also true about languages. When the urban world loses a

language, the rural world follows the tendency.[32]

There is, therefore, a strong need for an

effective language planning in Bishkek to implement bilingualism among its

inhabitants. Otherwise, Kyrgyz may have its days numbered in Bishkek, the cultural,

political and industrial nucleus of Kyrgyzstan, which might doom the language

forever.

[1]Abazov, R. Historical Dictionary of

Kyrgyzstan, The Scarecrow Press, Oxford, 2004, p. 1.

[2]Abazov, R. Historical Dictionary of

Kyrgyzstan, The Scarecrow Press, Oxford, 2004, p. 8.

[3]National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. Population

and Housing Census of the Kyrgyz Republic of 2009, NSCKR, Bishkek, 2009 , p. 52.

[4]Landau, J. M. and

Kellner-Heinkele, B. Language politics in contemporary Central Asia,

I.B.Tauris, London, 2012, p. 119.

[5]International Republican Institute. Survey of Kyrgyzstan Public Opinion, February 2012, p. 19.

[6]National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. Population

and Housing Census of the Kyrgyz Republic of 2009, NSCKR, Bishkek, 2009 , p. 38.

[7]Comrie, B. The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1981, pp. 43-44.

[8]National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. Population and Housing Census of the Kyrgyz Republic of 2009, NSCKR, Bishkek, 2009 , p. 53.

[9]International Republican Institute. Survey of

Kyrgyzstan Public Opinion, February 2012, p. 64.

[10]Korth, B. Language Attitudes Towards Kyrgyz and Russian. Discourse, Education and Policy in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan, Peter Lang, Bern, 2005, p. 29; Odagiri, N. “A Study on Language Competence and Use by Ethnic Kyrgyz People in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: Results from Interviews”, Inter-Faculty, Vol. 3, 2012, pp. 7-8; O’Callaghan, L. “War of Words. Language Policy in Post-Independence Kazakhstan”, Nebula 1.3, 2004-5, pp. 208-209.

[11]Comrie,

B. The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1981, p. 21.

[12]Grenoble, L. A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Kluwer Academic Publishers, New York, 2003, p. 138.

[13]Comrie,

B. The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1981, p. 25.

[14]Grenoble, L. A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Kluwer Academic Publishers, New York, 2003, p. 142.

[15]Comrie,

B. The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1981, p. 25.

[16]Grenoble,

L. A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Kluwer Academic Publishers, New

York, 2003, p. 141.

[17]Grenoble,

L. A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Kluwer Academic Publishers, New

York, 2003, p. 155.

[18]Landau,

J. M. and Kellner-Heinkele, B. Language politics in contemporary Central Asia,

I.B.Tauris, London, 2012, p. 121.

[19]Schulter,

2003: 20-27 cited in Landau, J. M. and Kellner-Heinkele, B. Language politics

in contemporary Central Asia, I.B.Tauris, London, 2012, p. 120.

[20]Chotaeva, Ch. “Language as a nation building factor in Kyrgyzstan”, Central Asia and the Caucasus, No. 2(26), 2004, pp. 177-178.

[21]Peyrouse, S. The Russian Minority

in Central Asia, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington

D.C., 2008, p. 8.

[22]Pavlenko, A. “Russian in

post-Soviet countries”, Russian Linguistics, 32, 2008, p. 71.

[23]Chotaeva, Ch. “Language as a

nation building factor in Kyrgyzstan”, Central Asia and the Caucasus, No.

2(26), 2004, pp. 180; Eurasianet.

“Kyrgyzstan: Uzbek-Language Schools Disappearing”,

Eurasianet.org, 2013.

[24]OECD. Kyrgyz Republic 2010: Lessons from PISA, OECD Publishing, 2010, p. 181.

[25]Eurasianet.

“Kyrgyzstan: Uzbek-Language Schools Disappearing”,

Eurasianet.org, 2013.

[26]OECD. Kyrgyz Republic 2010: Lessons from PISA, OECD

Publishing, 2010, p. 183.

[27]Pavlenko,

A. “Russian in post-Soviet countries”, Russian Linguistics, 32, 2008, p. 71.

[28]OECD. PISA 2006: Science Competencies for Tomorrow’s World Executive Summary, OECD Publishing, 2007, pp. 47, 53.

[29]OECD. Kyrgyz Republic 2010: Lessons from PISA, OECD

Publishing, 2010, p. 146-148.

[30]Based on image at: http://bishkek-trolleybus.narod.ru/lines/map1.jpg

[31]Korth, B.

Language Attitudes Towards Kyrgyz and Russian. Discourse, Education and Policy

in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan, Peter Lang, Bern, 2005, p. 138.

[32]Crystal, D. Language Death, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 77.

Appendix

1

PART 1 – 1 ЧАСТЬ

Gender/Пол: Boy/Мальчик £ Girl/Девочка £

Age/Возраст:

Nationality (according to your

passport)

Национальность (в соответствии с паспортом):

Ethnicity (such as Dungan, Uyghur,

Kurdish, etc.):

Этническая принадлежность (как Дунган, Уйгур,

Курд и т.п.):

Common language spoken at home (Name

the language or languages):

Общий разговорный (употребляемый) язык дома (Назовите

язык или языки)

My mother’s family (grandparents,

uncles, aunties) speak (Name the language or languages):

Семья моей матери (дедушка и бабушка, дяди,

тетушки) говорят (Назовите язык или языки)

My mother speaks fluently (Name

the language or languages):

Моя мама говорит свободно (Назовите язык

или языки)

My father’s family (grandparents,

uncles, aunties) speak (Name the language or languages):

Семья моего отца (дедушка и бабушка, дяди,

тетушки) говорят (Назовите язык или языки)

My father speaks fluently (Name

the language or languages):

Мой отец говорит свободно (Назовите язык

или языки)

My father talks to my mother in (Name

the language or languages):

Мой отец разговаривает с мамой на (Назовите

язык или языки)

With my brothers and sisters I speak

(Name the language or languages):

С моими братьями и сестрами я говорю на (Назовите

язык или языки)

Bibliography

Abazov, R. Historical Dictionary of Kyrgyzstan, The Scarecrow

Press, Oxford, 2004.

Aminov, K., Jensen, V., Juraev, S., Overland, I.,Tyan, D.,

Uulu, Y. “Language Use and Language Policy in Central Asia”, Central Asia

Regional Data Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring, 2010, pp. 1-29.

Chotaeva, Ch. “Language as a nation building factor in

Kyrgyzstan”, Central Asia and the Caucasus, No. 2(26), 2004, pp. 177-184.

Comrie, B. The Languages of the Soviet Union. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, 1981.

Crystal, D.

Language Death, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

Eurasianet.

“Kyrgyzstan:

Driving the Russian Language from Public Life”, Eurasianet.org, 2011, http://www.eurasianet.org/node/62916

Eurasianet.

“Kyrgyzstan: Uzbek-Language Schools Disappearing”,

Eurasianet.org, 2013, http://www.eurasianet.org/node/66647

Grenoble, L. A. Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Kluwer

Academic Publishers, New York, 2003.

Hiro, D. Inside Central Asia, Overlook Duckworth, New York,

2009.

Hou, D. “Education Reform in the Kyrgyz Republic”,

Knowledge Brief, vol. 40. World Bank,

2011.

International Republican Institute. Survey of Kyrgyzstan

Public Opinion, February 2012, http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2012%20April%2011%20Survey%20of%20Kyrgyzstan%20Public%20Opinion,%20February%204-27,%202012.pdf

Kelner, C. Social Reproduction in Transition: Kyrgyzstani

Language Policies and Higher Education. Unpublished MA thesis. Central European

University, Budapest, 2012.

Kenez, P. A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to

the End. 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

Korth, B. Language Attitudes Towards Kyrgyz and Russian.

Discourse, Education and Policy in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan, Peter Lang, Bern,

2005.

Landau, J. M. and Kellner-Heinkele, B. Language politics in

contemporary Central Asia, I.B.Tauris, London, 2012.

McMann, K. M. Economic Autonomy and Democracy-Hybrid Regimes

in Russia and Kyrgyzstan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

Millar, J. R. (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Russian History (Volumes

I-IV), Macmillian Reference, New York, 2006.

National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Population and Housing Census of the Kyrgyz Republic of 2009, NSCKR, Bishkek,

2009.

O’Callaghan, L. “War of Words. Language Policy in

Post-Independence Kazakhstan”, Nebula 1.3, 2004-5, pp. 197-216.

Odagiri, N. “A Study on Language Competence and Use by Ethnic

Kyrgyz People in Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan: Results from Interviews”,

Inter-Faculty, Vol. 3, 2012, pp. 1-24.

OECD. PISA 2006: Science Competencies for Tomorrow’s

World Executive Summary, OECD Publishing, 2007, http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/39725224.pdf

OECD. Kyrgyz Republic 2010: Lessons from PISA, OECD

Publishing, 2010, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264088757-en

Pavlenko, A. “Russian in post-Soviet countries”, Russian

Linguistics, 32, 2008, pp. 59–80.

Peyrouse, S. The Russian Minority in Central Asia, Woodrow

Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington D.C., 2008.

Suny, R.G. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Russia. The

Twentieth Century. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

Tyson, M.J. Russian Language Prestige in the States of the

Former Soviet Union. Unpublished MA

Thesis. Naval Postgraduate School, Monterrey CA, 2009.

UNESCO, 2010. World Data on Education VII Ed. 2010/11 –

Kyrgyz Republic, 2010 http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/WDE/2010/pdf-versions/Kyrgyzstan.pdf

Wright, S. (ed.) Language

Policy and Language Issues in the Successor States of the Former USSR, Multilingual Matters,

Clevedon, 2000.

*Siarl Ferdinand - PhD Candidate in Bilingual Studies at University of Wales Trinity Saint David. He is currently working as an English language instructor at the American University in Bulgaria. e mail: yeth_kernewek@yahoo.co.uk

**Flora Komlosi - English language instructor at the American University in Bulgaria. Her research interest is in the area of motivation for learning foreign languages. e mail: flora.komlosi@yahoo.co.uk

© 2010, IJORS - INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES